Rievaulx Abbey was a Cistercian abbey in Yorkshire (Photo: Getty/Andrea Pucci)

This interesting item which I’ve had ready to go for over a year reminds me a little of A Time to Keep Silence. Given the state of the world now, it is perhaps even more relevant.

By Sarah Sands

First published in inews.co.uk

As editor of the Today programme, I was addicted to news – but now I’m seeking monastic peace from the world. Sarah Sands believes there is a forgotten wisdom in monasteries that provides an answer to the tumult of our times – monks and nuns have acquired a hidden knowledge of how to live.

On a winter’s day, in which the sky hangs like a flat sheet over Norfolk, I look out at the remains of a 13th-century monastery wall. It’s in the field at the edge of my garden – all that remains of Marham Abbey, a Cistercian nunnery destroyed by Henry VIII.

The king found nothing of note in the abbey – the total loot was worth £46 – yet its last remnants exist as a centre of gravity in my life. The lessons of monastic life are contained within this wall, lessons that have increasingly offered guidance and inspiration for me in times of stress.

The great English Cistercian monastery is Rievaulx Abbey in North Yorkshire, a five-hour drive from my home. Deciding that I needed to learn more about the community who built my wall, one day in 2019 I set off with an inexplicable sense of purpose. I drove past miles of skeleton trees, descending into a remote valley of the river Rye in the North Yorkshire moors. The hidden nature of Rievaulx makes its revelation all the more heart stopping.

St Aelred, abbot of Rievaulx monastery, once said, ‘everywhere peace, everywhere serenity and a marvellous freedom from the tumult of the world”(Photo: Getty/Ian Forsyth)

There, alone, I wandered through the vistas of columns and framed views of stirring countryside. I imagined the first monks who sheltered there under the rocks of the valley and among the elm trees. The remoteness of monasteries – best viewed from the heavens – is in their essence; it is a rejection of the material world, its rhythms and its values.

The monks lived by sunrise and sunset and spent their time between in learning, meditation and manual labour. This inner concentration buoyed them in an extraordinary weightlessness. In the 12th century, St Aelred, abbot of Rievaulx monastery said: “Everywhere peace, everywhere serenity and a marvellous freedom from the tumult of the world.”

When I returned from Rievaulx, I was changed. I saw my wall in a different light. My sense of kinship with it deepened and my curiosity tingled. I saw that it was part of a network of monasteries across the country; ruined, silent, consigned to history, they all had stories to tell.

I began travelling to more and more of them, exploring them one by one – and travelling to monasteries around the world, too, from Greece to Egypt, from Japan to Bhutan, journeys I’ve been since reflecting on for my book The Interior Silence.

There was wisdom in these institutions. There was medicine. From the monasteries came both universities and hospitals, and the monks showed an early understanding of what we now call mental health.

The monastic way of living intrigued me – it had become a secret corner of my life. My work is in London, but Norfolk is my place of sanctuary. The wall represents something antithetical to my London life. It is the still small voice that provides a contrast to the needy, WhatsApp-ing, power-conscious world of politics and media.

‘Today’ and tomorrows

The job that I held when I visited Rievaulx was editing the BBC’s flagship news and current affairs show, the Today programme, during the most politically and socially fractious of periods. People were angry about whether or not Britain should leave the EU, and Today was a lightning rod.

I was responsible for the running order of the show, which was a work in progress over 24 hours. My phone beeped incessantly. There were months when it buzzed hysterically between 3am and 5am, until I realised that, apart from all the journalistic messages, I had somehow become the switchboard for all the taxis ordered by the BBC news department.

Skimming six hours sleep a night and ever part of a jittery and constant news conversation, I was finding it hard to switch off.

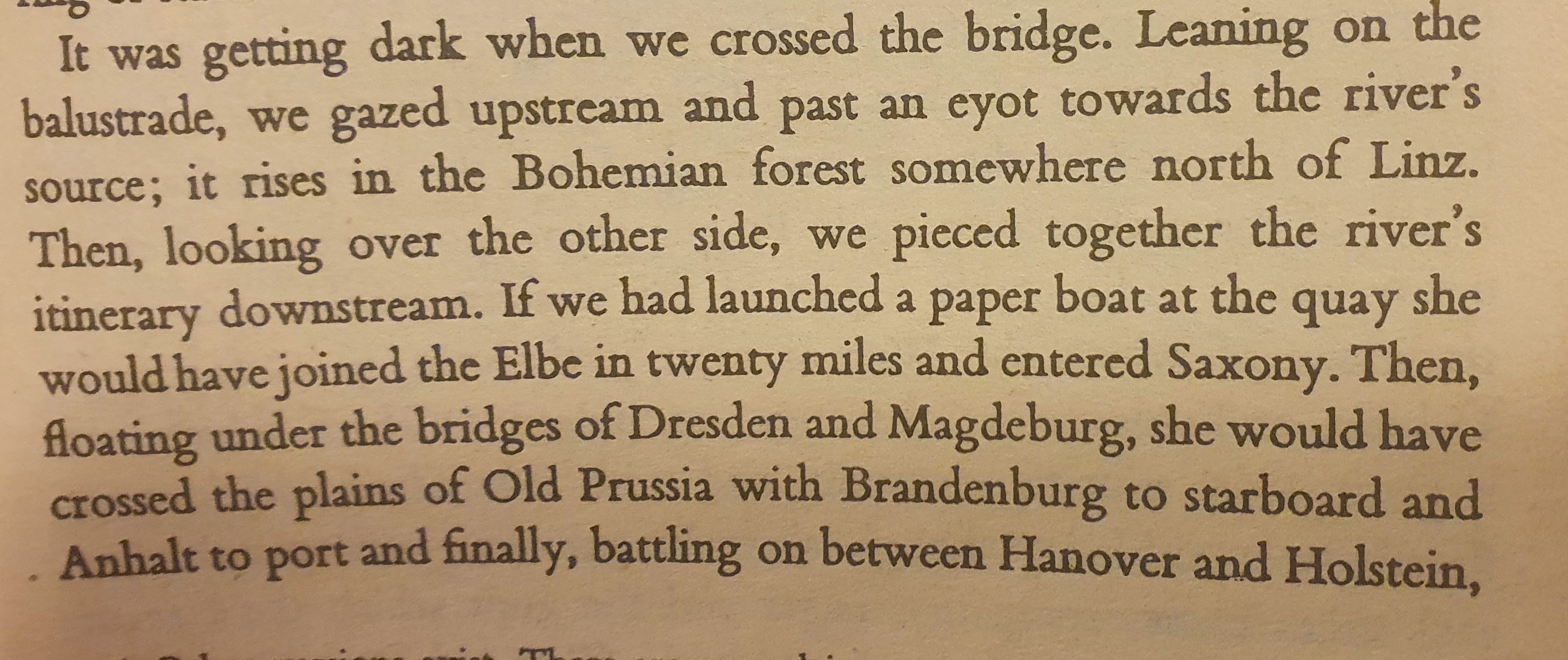

One night, during which I simply could not sleep, I picked up a book. It was a slim volume, called A Time to Keep Silence, by the great adventurer Patrick Leigh Fermor. Published in 1957, it is an account of his sojourns at three wonderful French monastic buildings: the Abbey of St Wandrille, Solesmes Abbey and La Grande Trappe.

In the book, Leigh Fermor confessed to depression and anxiety; he yearned for peace and stillness. “In spite of private limitations I was profoundly affected by the places I have described,” he wrote.

“The kindness of the monks has something to do with this. But more important was the discovery of a capacity for solitude and (on however humble a level compared to that of most people who resort to monasteries) for the recollectedness and clarity of spirit that accompany the silent monastic life.”

There is a wisdom in the monasteries which answers the affliction of our times (Photo: Getty/Ian Forsyth)

He also experienced a higher plane of sleeping: “After initial spells of insomnia, nightmare and falling asleep by day, I found that my capacity for sleep became more remarkable and my sleep was so profound that I might have been under the influence of some hypnotic drug… Then began an extraordinary transformation: night shrank to five hours of light, dreamless and perfect sleep, followed by awakenings full of energy and limpid freshness.

Can you imagine this? City sleep resembles an operating theatre of lights, movement and bleeping devices. We seek instant remedies for sleep, as for everything else. Of course, I am not going to give up alcohol, but I will throw in a herbal tea at the end of the evening. And I know to close the day with a book, although every few paragraphs my hand slides towards my iPhone, just to check messages or to Instagram.

Sometimes I try to meditate for a few minutes, which only jolts my memory of the emails I should have sent. This is not the path to the dreamless and perfect sleep of which Leigh Fermor writes.

The following day, I bumped into my friend Tom Bradby, the ITV news anchor who had been off work for many months, suffering from extreme insomnia. He had recovered but had not forgotten his state or the causes of it. He had a new awareness of the meaning of what he called “the worried mind”.

I reflected again on what Leigh Fermor had written: “In spite of private limitations, I was profoundly affected [by the monasteries].” This was how I felt about my Norfolk ruins. I knew they touched me deeply but did not know why and certainly did not attribute it to any virtue on my part.

There is a wisdom in the monasteries which answers the affliction of our times. Renouncing the world, the monks and nuns have acquired a hidden knowledge of how to live. They labour, they learn and they master what is described as “the interior silence”. Some orders are in permanent retreat, but others are expected to maintain the stillness of self in the midst of public bustle.

How can they do that? Is the virtue of interior silence something that can prevail in an era of peak technological distraction? I was beginning to question my 5G life. The connectivity, the drip feed of news, the superficiality of politics.

As Radio 4 listeners will know, in the middle of the Today programme is Thought for the Day, a three-and-a-half-minute sermon by a religious figure. It is an anomaly in a daily news show, but I have come to appreciate it as an oasis of reflection. News counts but meaning matters more.

I experienced that juxtaposition of connectivity and meaning at a dinner for the tech industry in the same week that I had read Leigh Fermor’s book from cover to cover – properly read it, rather than speed-read it as I usually do.

The conversation at the tech gathering was all about pace of change and personal realisation. We are driven by multiples of success and scale. Meanwhile, at my table, a broadcaster was looking furiously at her Twitter feed because a political joke had started a bush fire of condemnation. By the end of the evening, her resignation from the BBC was being demanded. This was a time of maximum hubris, before the arrival of the great reckoning.

The ubiquity of news media is a form of hubris, at odds with monasticism. Aggravated by social media, the journalistic impulse is exhibitionism and noise and entitlement.

The former Conservative strategist Lynton Crosby, who campaigned for Boris Johnson as London mayor and later as prime minister, said to me that people were motivated by jobs, money and family. His candidates won, he said, because he and they understood this. The remarkable thing about the monasteries is that they are inspired by none of these things. They are there on behalf of humanity, suspended between heaven and earth.

What if I were able to step away, I thought, even in the midst of political and media battle? There is a history of spiritual retreat after all.

Lockdown isolation

After three years of editing the Today programme, I left the BBC last September. I had made the decision at the start of 2020. The addiction to news had become corrosive to me and I had learned how to exist outside the news cycle, thanks to contemplative trips to monasteries. My hectic, distracted mind had experienced stillness.

News is generally regarded as a form of enlightenment but it is often just information wrapped in judgement, or worse, incitement. News demands drama and hyperbole. I remember when I was the editor of The Sunday Telegraph more than a decade ago, looking at a headline claiming local ‘fury’ over a piece of planning permission. I remarked to the news editor that having read the quotes from residents it seemed more a case of mild irritation than fury. The news editor responded wryly: “Irritation isn’t a headline word.”

I was planning to visit more monasteries ahead of my departure. Easter week was meant to have been spent in Salzburg, at the Nonberg Abbey – otherwise known as the setting for The Sound of Music – but in March last year lockdown arrived. Flights were halted, hotels closed. Monasteries continued in their customary state of self-isolation, and I was unable to reach them.

The Government demanded that the population return to their homes: mine was in Norfolk, in the remains of Marham Abbey. A monument to mortality and the futility of secular ambition. Henry VIII destroyed this monastery but could not destroy its meaning; perhaps because its endurance was based on acceptance of powerlessness.

Newspapers carried photographs of vats of beer and wine being tipped away. This was the London economy – bars and coffee shops. Farewell to my working life.

The existence that I was trying to escape suddenly seemed unbearably delightful. I watched television scenes of dinner parties or concerts as if through a looking glass. My bank statements read like an historical archive. Soho House, Joe the Juice, Caffè Nero, Daniel Galvin and, in the final days, Wigmore Street Pharmacy, Boots, Boots, Boots.

The Today programme was being produced remotely, and I spent hours pacing the garden on Zoom. What were the latest death figures? What was the state of the Prime Minister’s health? The country staked its identity on the principle of caring for the sick. A principle begun in its monasteries. Indeed, St Thomas’ Hospital in London, where the Prime Minister was treated, grew out of a priory.

Like everyone else, I was separated from what and whom I knew and loved. My younger son FaceTimed me from Hong Kong. He told me that he would not be coming home for his summer break because of the strict rule of quarantine. My elder son sent me a photograph of my grandson, only 20 miles away, but beyond reach now. My daughter went into lockdown in London, the epicentre of the virus. Every family had a story to tell of separation.

Monasticism teaches that you can love and participate, while being absent. This was what I had to learn; to appreciate relationships in the abstract. To delight in the existence of others without physical engagement in their lives.

I would describe the feelings I associated with the wall in my garden during those weeks of isolation as intense serenity and a sense of belonging. Most of all, I associated it with birdsong. The trees surrounding the abbey remains were full of birds – blackbirds, blue tits, finches, wrens, chiffchaffs, robins, rooks and, descending from the wide skies, the first swallows.

There was one thing I wished to learn in isolation: the distinctive differences in birdsong. On the first day I picked up the alarm call of the blue tits and the different whistles of the great tit. I wondered at the lung capacity of the tiny wrens. The busy sound of the chiffchaff will always remind me of this time, this period of death tolls and birdsong.

I hope to be visiting more monasteries soon, when life opens up again, but I’m lucky to have my wall. There is something about the melancholy ruins against a Norfolk sky that reminds you that a contemplative life has a natural setting and that the endless striving and building around it will not last. The tranquil message of my ruins of Marham Abbey and the great Rievaulx is humility. Personal ambition is an impediment, not a triumphant force.

This is an edited excerpt from The Interior Silence: My Encounters with Calm, Joy, and Compassion at 10 Monasteries Around the World by Sarah Sands. Buy it here.