Paddy’s passport issued in Munich to replace the one stolen

As Christmas approaches each year, it is a time to remember Paddy’s departure from London on a steamer in 1933. For me those first few weeks offer some of the best stories in A Time of Gifts occurring in that short period into the New Year when he was not only acclimatising to the frozen weather but the new surroundings and culture that he found himself in. Time and war have almost totally changed everything. This timely article is a reminder of Paddy’s genius and affability, and what was lost to us in the war.

By Michael Duggan

First published in The Critic

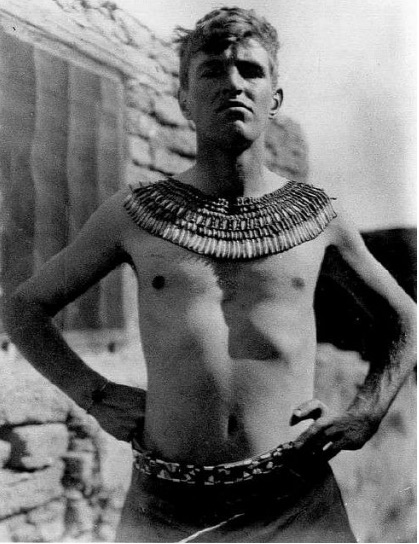

It is now ninety years since Patrick Leigh Fermor raced down the steps of Irongate Wharf, in the shadow of Tower Bridge, and boarded a steamer bound for the Hook of Holland. There were no other passengers. From Rotterdam — he had decided — he would walk his way across the breadth of Europe to what he persisted in calling Constantinople (or, if not, Byzantium). Later, a couple of hours before dawn, he was on a train from the Hook to the city, the solitary passenger once again. The snow and darkness completed the illusion of slipping into Europe through a secret door.

“Paddy” spent barely an hour in Rotterdam. It occupies barely more than a page of A Time of Gifts, the book which recounts all that happened on the first part of his trek, from Holland right up to the Hungarian border. Nevertheless, two human qualities take centre stage in the Dutch port and remain there for more or less the entirety of the book. The Rotterdam episode also sounds a bass note of sadness about the fate of Europe that must accompany any reading of Fermor.

The first of the human qualities is the kindness of strangers — in this case, the kindness of the owner of a quayside café, a “stout man in clogs”, Fermor’s first host on European soil. As dawn breaks, whilst the landlord polishes his glasses and cups, arranging them “in glittering ranks”, Paddy has the best fried eggs and coffee he has ever eaten. When he is finished and heads for the door, the stout man asks where he is going:

I said “Constantinople.” His brows went up and he signalled to me to wait: then he set out two small glasses and filled them with transparent liquid from a long stone bottle. We clinked them: he emptied his at one gulp and I did the same. With his wishes for godspeed in my ears and an infernal bonfire of Bols and a hand smarting from his valedictory shake, I set off. It was the formal start of my journey.

Again and again over the course of his trek, Fermor, who was only eighteen at the time, encountered this tradition of benevolence to the wandering young. In Cologne, he falls in with Uli and Peter, crewmen on a barge carrying cement to Karlsruhe, who show him a bawdy and hilarious old time, which includes going to a Laurel and Hardy film together. They feed him in their cabin on fried potatoes and cold lumps of pork fat. In Heidelberg, he is taken in by the owners of the Red Ox Inn who wash his clothes and give him a free bed for the night. In Hohenaschau, a slip of paper signed by the Bürgermeister entitles him to supper, a mug of beer, a bed and a morning bowl of coffee, “all on the parish”.

Paddy thanks God that he had put “student” on his passport (even though, at the time, he wasn’t really a student in any formal sense). The word was “an amulet and an Open Sesame. In European tradition, the word suggested a youthful, needy and earnest figure, spurred along the highways ( … ) by a thirst for learning — ( … ) a fit candidate for succour”.

The second quality that shines out of the Rotterdam episode, and out of page after page of A Time of Gifts, is one belonging to Paddy himself. This was his inimitable and expansive form of erudition, encompassing literature, religion, art and architecture, combining humility and panache in perfect, improbable harmony. The first person he sees in Rotterdam is Erasmus, in statue form, with snow piling up on his shoulders; later, in Cologne, he ends up discussing the correct pronunciation of Erasmic Latin with a couple of young Germans in the house of the widow of a Classics professor.

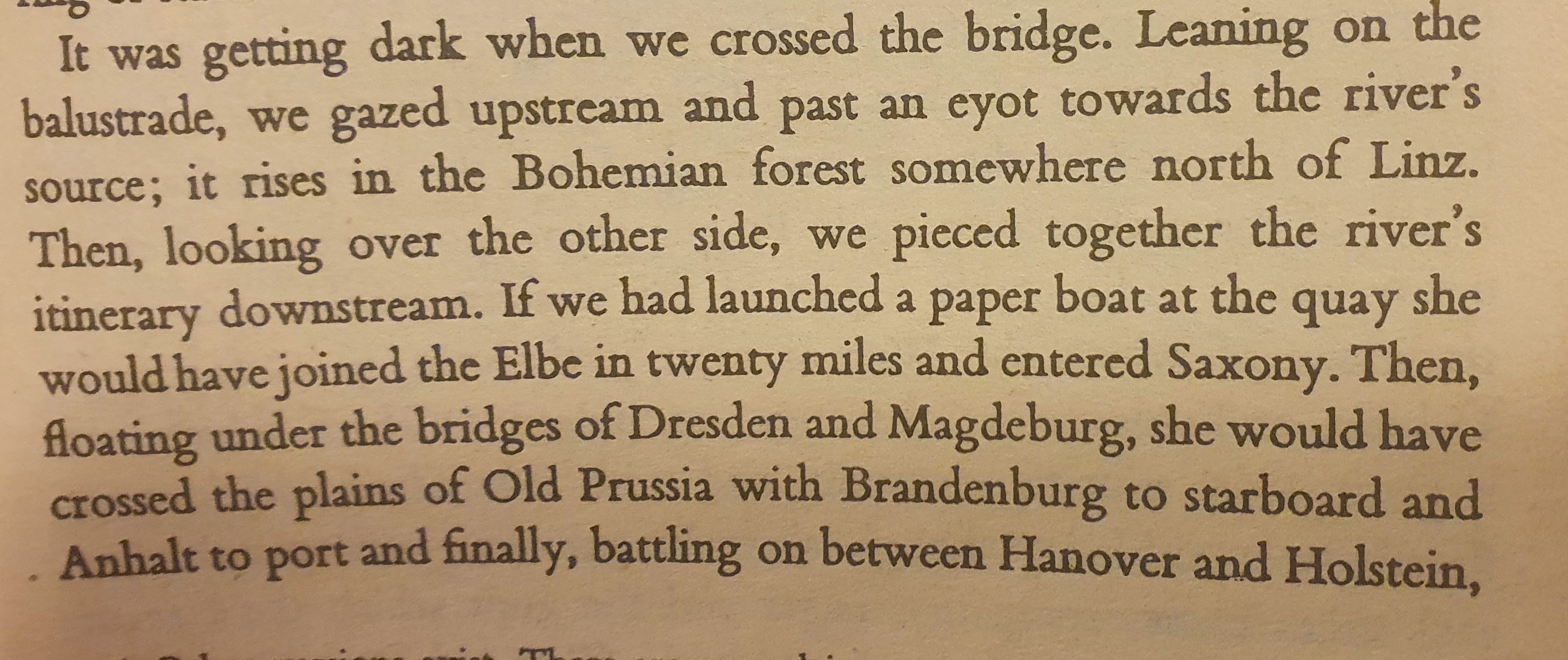

Fermor’s erudition was a constant stimulus to his imagination. Entering the Groote Kirk of Rotterdam in the dim early morning light, his familiarity with Dutch painting allows him to fill the empty church with “those seventeenth-century groups which should have been sitting or strolling there: burghers with pointed corn-coloured beards — and impious spaniels that refused to stay outside — conferring gravely with their wives and their children, still as chessmen, in black broadcloth and identical honeycomb ruffs”. He is at this again, three or four days later, when his legs have taken him as far as Brabant. Here it is the “Hobbema-like avenues of wintry trees” leading to the gates of “seemly manor houses” that set him off, exploring the interiors of these houses in his imagination. Every step of the way, Paddy takes this erudition with him, seeing correspondences, formulating theories, letting his imagination soar, and having a whale of a time inside his head.

It is not possible to talk about Fermor in Rotterdam without talking about what happened to that city a few years later. Paddy noted it himself: this beautiful place was “bombed to fragments” in May 1940 (“I would have lingered, had I known”). Aerial images of the destruction are chilling: one can see the pattern of the streets, but the buildings are all gone. The eye is drawn to the quaysides where the café Fermor visited must have stood. There’s nothing there.

The new Rotterdam built on the rubble of the old is not a pretty sight. In the words of the English travel writer Nick Hunt, who in 2011 set off to replicate Fermor’s “great trudge”, the continuity between the two cities was “absolutely severed”: “The Rotterdam of the Middle Ages had been blasted into the realm of fairy tales, and the new reality of McDonald’s and Lush, Starbucks and Vodafone had rushed to fill the vacuum. The destruction seemed less an act of war than apocalyptic town planning, a Europe-wide sweep of medieval clutter to clear the way for the consumer age.”

The fate of Rotterdam highlights a facet of A Time of Gifts and its successor Between the Woods and the Water (which takes us from Fermor’s arrival in Hungary to the Iron Gate gorge on the Danube, separating the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and Romania). The writing is ebullient, funny, joyful and true both to the youth Patrick Leigh Fermor was and to the man he became — some people found him an insufferable show-off, but most who knew him craved his company — but Paddy knew as he was writing (just as we know as we are reading) that the Rotterdam of then, along with the Europe of then, have gone.

It was, of course, already going when Fermor disembarked at the Hook of Holland: Hitler had been Chancellor for nearly a year. Crossing Germany, Fermor saw Nazis up close more than once. Writing about these encounters, his habitual powers of observation are not warped by any retrospective performative disgust, which must have been tempting to indulge in, so many years after the events described and with no chance of someone turning up to contradict his account. He sees humans in uniforms, being slowly poisoned by those same uniforms (or by the sight of them) and by what they represent, but remaining human even in their descent into dark obsessions and moral squalor. According to Artemis Cooper, Patrick Leigh Fermor’s biographer, Communism never exerted any pull on him, any more than Fascism: both were “ready to destroy everything he loved about European civilization in order to build their aggressively utilitarian superstates”.

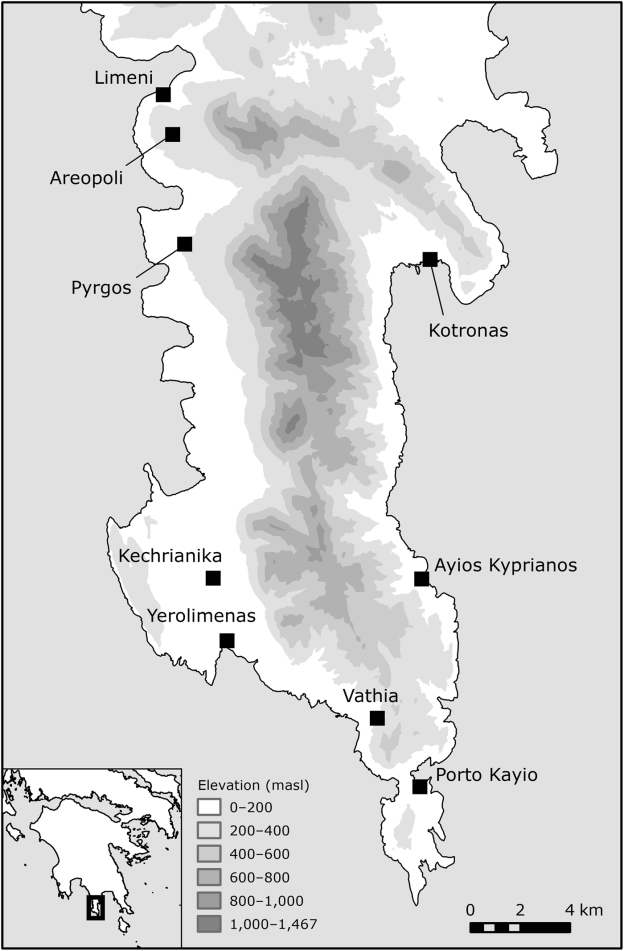

On his trek, Fermor was one of the last travellers able to move amongst the remnants of old Europe left behind by the First World War — the customs, the beliefs, the strange dialects, the hidden tribes, the curious institutions — either before they were finally swept from the board (some of them into a basket labelled “heritage”) by the Second World War or by modernity hitting top stride; or before they disappeared behind the Iron Curtain and were rendered extinct.

The great severing of Europe, in time and space, hit Patrick Leigh Fermor personally. In 1935, in Athens, he met and fell in love with Balasha Cantacuzène, sixteen years his elder, a princess and painter belonging to one of the great dynasties of eastern Europe. They spent much of their four years together on the run-down family estate in Moldavia, Rumania, from whence Paddy returned to England immediately after Britain declared war on Germany in order to sign up. He later wrote an account of the last day of peace in Moldavia when he rode with others in a cavalcade of horses and an old open carriage, through sunlit fields and vineyards, to a mushroom wood. Coming home, “The track followed the crest of a high ridge with the dales of Moldavia flowing away on either hand. We were moving through illimitable sweeps of still air”.

Balasha Cantacuzene ended up marooned behind the Iron Curtain. It was over a quarter of a century before she and Patrick Leigh Fermor saw one another again and for the last time. The Europe they knew had been extinguished forever.

You can listen to an AI generated reading of this here.

About The Critic. It is a monthly magazine for politics, ideas, art, literature and much more edited by Christopher Montgomery. The Critic says it exists to push back against a self-regarding and dangerous consensus that finds critical voices troubling, triggering, insensitive and disrespectful. The point is not provocation or trolling. The point of honest criticism is to better approach truth, not deny its possibility. You can find out more and subscribe here. This blog has no affiliation with The Critic.

May 11th 1944

May 11th 1944

10th May 1944

10th May 1944

8th May 1944

8th May 1944

7th May 1944

7th May 1944

6th May 1944

6th May 1944

5th May 1944

5th May 1944

4th May 1944

4th May 1944

3rd May 1944

3rd May 1944

2nd May 1944

2nd May 1944

1st May 1944

1st May 1944

30th April 1944

30th April 1944

28th April 1944.

28th April 1944.

27th April 1944.

27th April 1944.