Patrick Leigh Fermor and William Stanley Moss (top row, second and third from left) with other members of the group that abducted the German general Heinrich Kreipe, Crete, April 1944. Estate of William Stanley Moss/Sir Patrick Leigh Fermor Archive/National Library of Scotland

In one of the most audacious feats of World War II, two British undercover agents and a group of Greek partisans in Nazi-occupied Crete kidnapped General Heinrich Kreipe, the commander of the German garrison’s foremost division. Over eighteen days, with a net of enemy troops tightening around them, they marched him across the island’s mountains to be transported on a motor launch to Egypt.

By Colin Thubron

First published in the New York Review, March 11 2021

“Of all the stories that have come out of the War,” a radio announcer declared triumphantly, “this is the one which schoolboys everywhere will best remember.” The exploit was celebrated in 1950 by its deputy leader William Stanley Moss in his book Ill Met by Moonlight, which became a popular movie produced and directed by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger.

The leader of the operation, Patrick Leigh Fermor (played onscreen by Dirk Bogarde), was to become a legendary figure in postwar Britain and Greece, as well as the most revered travel writer of his generation. But his full account of the action, Abducting a General: The Kreipe Operation in Crete, wasn’t published until several years after he died. Beside its sheer drama and the frequent fineness of Leigh Fermor’s writing, the story resonates with half-answered questions. Was the exploit worth it? What, if any, was its strategic effect? Above all, were the atrocities visited afterward on Cretan villages by the Germans an act of vengeance for the abduction?

Recent years have seen a surge of interest in Leigh Fermor’s life and work. Since his death in 2011, a fine, full-scale biography by Artemis Cooper has appeared; his archive at the National Library of Scotland has been mined for new material; and two volumes of his letters, Dashing for the Post and More Dashing, in which he recounts inter alia his periodic returns to Crete, were edited by Adam Sisman. On the last of these journeys, in 1982, Leigh Fermor was delighted—and perhaps relieved—at his rapturous reception from his Cretan comrades-in-arms, still inhabiting his wartime haunts: whiskery old men now, who feasted him mountainously for days.

Their memories are long and bitter. The Nazi occupation of Crete, and of all Greece, was a particularly brutal one, in which perhaps 9 percent of the nation’s population perished, and almost the entire Jewish population of the island, destined for death camps, was drowned when their transport ship was mistakenly torpedoed by a British submarine. Hundreds of villages, including many in Crete, were razed.

These memories have recently surfaced again in the rhetoric of Greek politicians. Germany, ironically, is Greece’s main creditor. In protesting German stringency in the face of their towering debt, the Greeks raised the old question of war reparations, maintained by Germany to have been settled in 1990. In 2015 the Greeks demanded a further $303 billion for damaged infrastructure, war crimes, and repayment of a Nazi-enforced loan from Greece to Germany. The present Greek prime minister has pursued this less stridently than his predecessor, but the demand remains.

This rankling bitterness would not have surprised those members of the British Special Operations Executive (SOE) who operated undercover in the Cretan mountains, and who witnessed firsthand the Greek hatred of their oppressors. Part of Leigh Fermor’s motive in producing his own account of Kreipe’s abduction was to pay tribute to the intransigent courage and resolve of the local inhabitants.

Yet the writing of the operation originated by chance. In 1966 the editor of Purnell’s History of the Second World War, an anthology of feature-length essays, commissioned Leigh Fermor to record the operation in five thousand words. But Leigh Fermor was not one for shortcuts, and he produced over 30,000 words, almost a year late. Eventually a version appeared in Purnell’s History, stripped down by a professional journalist, and shorn of most of the color, drama, and anecdote that characterized the original.

It is easy to see how this original—published as Abducting a General —exasperated the Purnell’s History editor. From the start, although it records every tactical move, it reads more like a vivid and expansive adventure story than a military report. On the night of February 5, 1944, signal fires glitter on a narrow Cretan plateau as Leigh Fermor parachutes out of a converted British bomber. It is the start of things going wrong. Clouds close in, and his fellow officer “Billy” Moss cannot drop down after him. It is two months before they rendezvous on the island’s southern shore, after Moss has arrived from Egypt by motor launch.

Leigh Fermor was twenty-nine, Moss only twenty-two, but both had seen hard war service. Moss, a captain in the Coldstream Guards, had fought in North Africa, but had no previous experience of guerrilla warfare. Leigh Fermor, on the other hand, had already been in Crete fifteen months, disguised as a shepherd, gathering intelligence and organizing resistance. He spoke fluent Greek and had struck up warm friendships among the andartes, the region’s guerrillas.

The island where they landed was the formidable German Festung Kreta, Fortress Crete, garrisoned by some 50,000 soldiers, but menaced by a hinterland of lawless mountain villages. The British target at first had been the brutal General Friedrich-Wilhelm Müller (who would be executed for war crimes in 1947). But he had recently been replaced by General Kreipe, a veteran of the eastern front, who for propaganda purposes was considered an equally promising prize.

Such a kidnapping would undermine the morale of the German forces, Leigh Fermor wrote; it would inspirit the resistance (which had suffered recent reverses) and prove a setback to the Communist propagandists who were seeking to divide the Greek island as they had the mainland. He proposed to his SOE superiors in Cairo that the action should be “an Anglo-Cretan affair”:

It could be done, I urged, with stealth and timing in such a way that both bloodshed, and thus reprisals, would be avoided. (I had only a vague idea how.) To my amazement, the idea was accepted.

In a curious lapse of German security, Kreipe was driven unescorted each evening five miles from his divisional headquarters to his fortified residence. At a steep junction in the road Leigh Fermor, Moss, and a selected band of andartes lay in wait after dark until a flashed warning from an accomplice signaled the car’s departure. As the Opel’s headlights approached, the two SOE officers, wearing the stolen uniforms of German corporals, flagged it down with a traffic policeman’s baton.

On one side Leigh Fermor saluted and asked in German for identity papers, then wrenched open the door and heaved the general out at gunpoint. On the other, Moss, seeing the chauffeur reach for his revolver, knocked him out and took his place at the wheel. Meanwhile the Cretan guerrillas manacled the general, bundled him into the back of the Opel, and dragged the driver to a ditch. Leigh Fermor put on the general’s hat, three andartes held the general at knifepoint on the seat behind, and Moss drove off in the direction that the enemy would least expect: toward the German stronghold of Heraklion.

Along the road, and within the city’s Venetian walls, the general’s car, with its signature mudguard pennants, cruised past raised barriers and saluting sentries. In the blacked-out streets the car’s interior was almost invisible. Moss drove through twenty-two checkpoints. Occasionally Leigh Fermor, his face shadowed under the general’s hat, returned the salutes. Then the car exited the Canea Gate and they went into the night.

In the eighteen days that followed, the party often split and reformed. The Opel was abandoned near a bay deep enough to give the impression that a British submarine had spirited the general away. Anxious that no reprisals should be taken against the Cretans, Leigh Fermor pinned a prepared letter to the front seat:

Gentlemen,

Your Divisional Commander, General Kreipe, was captured a short time ago by a BRITISH Raiding Force under our command. By the time you read this both he and we will be on our way to Cairo.

We would like to point out most emphatically that this operation has been carried out without the help of CRETANS or CRETAN partisans and the only guides used were serving soldiers of HIS HELLENIC MAJESTY’S FORCES in the Middle East, who came with us.

Your General is an honourable prisoner of war and will be treated with all the consideration owing to his rank. Any reprisals against the local population will thus be wholly unwarranted and unjust.

Beneath their signatures they appended a postscript: “We are very sorry to have to leave this beautiful motor car behind.” Other signs of British involvement—Players’ cigarette stubs, a commando beret, an Agatha Christie novel, a Cadbury’s chocolate wrapper—were scattered in the car or nearby.

At daybreak the general was hidden in a cave near the rebellious village of Anoyeia. Leigh Fermor was still in German uniform when he entered the village with one of the andartes. “For the first time,” he wrote,

I realised how an isolated German soldier in a Cretan mountain village was treated. All talk and laughter died at the washing troughs, women turned their backs and thumped their laundry with noisy vehemence; cloaked shepherds, in answer to greeting, gazed past us in silence; then stood and watched us out of sight. An old crone spat on the ground…. In a moment we could hear women’s voices wailing into the hills: “The black cattle have strayed into the wheat!” and “Our in-laws have come!”—island-wide warnings of enemy arrival.

Yet his party’s progress soon came to resemble a royal procession. Guerrilla bands and villagers who recognized what had happened greeted them with jubilation and supplied food, guides, and escorts. But the going was very hard. Thousands of German troops were fanning across the mountains in search of them. Reconnaissance planes showered the country with threatening leaflets. Still, the group vanished from German sight among the goat tracks and canyons east of Mount Ida, whose eight-thousand-foot bulk straddles a quarter of the island. They crossed it in deep snow.

The general was a heftily built, rather dull man who trudged with them in reconciled gloom. He was not a brute, like Müller, but the thirteenth child of a Lutheran pastor whose chief worry, at first, was the loss of his Knights’ Cross medal in the scuffle. Sometimes a mule was found for him, but he fell twice, heavily. “I wish I’d never come to this accursed island,” he said. “It was supposed to be a nice change after the Russian front.”

On the slopes of Ida one dawn, where the two SOE officers and the general had been sleeping in a cave under the same flea-ridden blanket, Leigh Fermor placed the incident that he celebrated more than thirty years later in his A Time of Gifts. Gazing at the mountain crest across the valley, the general murmured to himself the start of a Horatian ode in Latin. It is one that Leigh Fermor knew (his memory was prodigious), and he completed the ode through its last five stanzas:

The general’s blue eyes had swivelled away from the mountain-top to mine—and when I’d finished, after a long silence, he said: “Ach so, Herr Major!” It was very strange. As though, for a long moment, the war had ceased to exist. We had both drunk at the same fountains long before; and things were different between us for the rest of our time together.

By now German troops were spreading across the long southern coast, from which the general would most likely be shipped to Egypt on a motor launch or submarine summoned by radio. But the radios and their clandestine operators were forced to relocate continually by German maneuvers, a crucial wireless-charging engine broke down, and messages (carried by runners) quickly became redundant as enemy troops took over remote beaches.

Yet Leigh Fermor’s party, sometimes guided by andartes’ beacons, slipped through the tightening cordon, and arrived at the defiant haven of the Amari Valley villages. It was another eight days, far to the west, before they found an undefended beach, made contact with a radio operator and with SOE headquarters in Cairo, and were promised a boat for the following night. In a last, ludicrous hitch, as Leigh Fermor and Moss attempted to flash the agreed Morse code signal for the rendezvous into the dark, they could not remember the code for “B.” But another of the group did; the motor launch returned, and they embarked for Egypt in euphoria, after shedding their boots and weapons for those comrades left behind.

It was soon after his capture, on the road beyond Heraklion, that General Kreipe, a tried professional soldier, asked, “Tell me, Major, what is the object of this hussar-stunt?”

In Abducting a General Leigh Fermor stresses morale: the blow to German confidence and the boost to Cretan resistance and pride. Immersed as he was in the emotional politics of the island, he felt the endeavor to be worth the risk. But others questioned it. Strategically it was irrelevant, and under his eventual interrogation the general yielded nothing of interest. “Kreipe is rather unimportant,” concluded the British War Office. “Rather weak character and ignorant.” The historian M.R.D. Foot, to Leigh Fermor’s irritation, called the abduction merely a “tremendous jape,” and even before the project was sanctioned, a senior SOE executive in Cairo, when asked if it should proceed, objected. The executive later wrote:

I made myself exceedingly unpopular by recommending as strongly as I could that we should not. I thought that if it succeeded, the only contribution to the war effort would be a fillip to Cretan morale, but that the price would certainly be heavy in Cretan lives. The sacrifice might possibly have been worthwhile in the black winter of 1941 when things were going badly. The result of carrying it out in 1944, when everyone knew that victory was merely a matter of months would, I thought, hardly justify the cost.

The cost may have been high. Some three and a half months after the general’s kidnapping, with the brutal Müller again the island’s commander, the Germans razed to the ground the recalcitrant village of Anoyeia. Müller’s order of the day was unequivocal. For Anoyeia’s longtime harboring of guerrillas and of British intelligence, for its murder of two separate German contingents, and for its complicity in Kreipe’s abduction:

We order its COMPLETE DESTRUCTION and the execution of every male person of Anogia who would happen to be within the village and around it within a distance of one kilometre.

Nine days later the Amari villages suffered the same fate, with 164 executed. The Greek newspaper Paratiritis, an organ of German propaganda, cited their support for the Kreipe abduction as the reason.

Patrick Leigh Fermor and Yanni Tsangarakis, Hordaki, Crete

Sir Patrick Leigh Fermor Archive/National Library of Scotland

Patrick Leigh Fermor (right) and Yanni Tsangarakis, Hordaki, Crete, May 1943

Leigh Fermor, by then convalescing in a Cairo hospital, was shattered by the news. Yet in retrospect he realized that some four months—an unprecedentedly long time—had elapsed before the German reprisals, which were usually instantaneous. There are historians who agree that citing Kreipe’s abduction was little more than an excuse, and that the real, unpublishable reason was that within two months the German forces were to start their mass withdrawal west across the island, exposing them to hostile regions like Amari that flanked their line of retreat. Colonel Dunbabin, Leigh Fermor’s overall commander, in his final report on SOE missions in Crete, shared this assessment, adding that Müller’s purpose was “to commit the German soldiers to terrorist acts so that they should know that there would be no mercy for them if they surrendered or deserted.”

When Leigh Fermor returned to the island soon after, his Cretan friends comforted him that the German revenge would have happened anyway: “These were consoling words; never a syllable of blame was uttered. I listened to them eagerly then, and set them down eagerly now.”

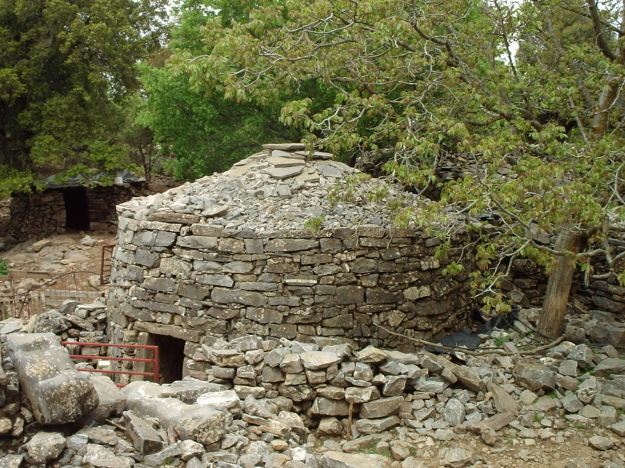

These thoughts and memories, of course, were written in retrospect. By the time of their composition in 1966 and 1967 Leigh Fermor had already completed a novella, a brief study of monastic life, and three travel books, including two fine descriptions of Greece, Mani and Roumeli. His Abducting a General, besides its value as a war document, slips readily into narrative reminiscent of a dramatic travel book, peppered with anecdote and irresistible asides. This is part of its allure. Military data merge seamlessly with the evocation of people and landscapes. A threatening storm is evoked in images of aerial pandemonium above a landscape of rotting cliffs and lightning-struck gorges. (One sentence of Proustian complexity runs to 138 words.) A cave in which the abduction party shelters from the exposing daylight is described with an eye for more than its military use:

It was a measureless natural cavern that warrened and forked deep into the rocks, and then dropped, storey after storey, to lightless and nearly airless stalactitic dungeons littered with the horned skeletons of beasts which had fallen there and starved to death in past centuries: a dismal den, floored with millennia of goats’ pellets, dank as a tomb.

The second, shorter section of the book is devoted to Leigh Fermor’s contemporary War Reports. Most valuable is his account of another evacuation. In September 1943 Italy surrendered to the Allies, and General Angelo Carta, commander of the 32,000-strong Italian Siena division occupying eastern Crete, was being hunted by the Germans. Through Carta’s counterespionage officer Franco Tavana, who handed over detailed Italian defense plans, Leigh Fermor organized the general’s escape, from a chaotic beachhead, to Egypt.

Even the reports are vivid with incident. On a clandestine visit to Tavana, Leigh Fermor hid under a bed from intruding Germans, “clutching my revolver, and swallowing pounds of fluff and cobwebs.” Crouched in the cellar of an Orthodox abbot, while sheltering from an enemy patrol—“It was a very near thing”—he glimpsed the Germans’ boots two feet above him through the floorboards. Elsewhere he describes how—heavily disguised—he taught a trio of drunken Wehrmacht sergeants to dance the Greek pentozali. It comes as a shock to realize that any Allied operative arrested on the island would be brutally tortured, then shot.

Leigh Fermor’s courage, generosity, and high spirits famously endeared him to the Cretans. He sang, danced, and drank with them. Naturally generous and uncritical, he describes almost every mountaineer as a model of hardiness and bravery: “Originality and inventiveness in conversation and an explosive vitality…. There was something both patrician and bohemian in their attitude to life.” He might have been describing himself. “We could not have lasted a day without the islanders’ passionate support.”

Among the Cretans Leigh Fermor most admired was a slight, high-spirited youth named George Psychoundakis (affectionately code-named the “Changebug”), whom the SOE used as a runner carrying messages over the mountains. This impoverished shepherd, whom Leigh Fermor’s confederate Xan Fielding called “the most naturally wise and instinctively knowledgeable Cretan I ever met,” could cover the harsh terrain at lightning speed, although he dressed in tatters and his disintegrating boots were secured with wire. After the Occupation ended he was mistakenly interned as a deserter and eventually went to work as a charcoal-burner to support his destitute family. It was at these times—in prisons, and in a cave above his work-site—that he labored on the book that became The Cretan Runner. It was translated by Leigh Fermor, who had discovered its author’s whereabouts after the war.

Patrick Leigh Fermor (right) and Yanni Tsangarakis, Hordaki, Crete, May 1943. Sir Patrick Leigh Fermor Archive/National Library of Scotland

Uniquely, it is a narrative written from the lowliest rank of the Greek resistance, by a man who was barely educated, and records four years as a dispatch carrier through the precipitous harshness of western Crete. Sometimes he rendezvoused with British arms drops or guided escaping Allied soldiers to the sea, and he evaded capture by swiftness, resourcefulness, and a profound knowledge of the terrain. He wrote:

My tactics on the march were to know few people, in order that few should know me, even if they were “ours” and good patriots. I kept my mouth shut with everybody, even to the point of idiocy, and these two things kept me safe to the end.

His book is an unaffected day-by-day drama, direct and demotic at best, only occasionally swelling into literary grandiloquence when he feels the subject (patriotism, the dead) requires it. Years later this self-taught prodigy translated the Iliad and the Odyssey into his vernacular Cretan, using the meter of the seventeenth-century romance Erotokritos, and was richly rewarded by the Athens Academy.

Leigh Fermor’s translation of this difficult work arose from his love of Cretan culture as well as respect for Psychoundakis. But his personal immersion in the island came at cost. One of his War Reports expands wretchedly on his accidental shooting of a partisan and great friend, Yanni Tsangarakis. Its recounting clouded his face even in old age. And misgivings that his Kreipe operation—brilliant and brave as it was—brought retribution on the island he loved may never have quite left him.

7th May 1944

7th May 1944

6th May 1944

6th May 1944

5th May 1944

5th May 1944

3rd May 1944

3rd May 1944

2nd May 1944

2nd May 1944

1st May 1944

1st May 1944

30th April 1944

30th April 1944

28th April 1944.

28th April 1944.

27th April 1944.

27th April 1944.