Some notes and observations by my friend Chris Lawson from the outstandingly successful Transylvanian Book Festival that took place in September. This was written as part of his entry to the Anthony Burgess/Observer literary competition and I am grateful that he let me publish this.

Transylvania : by Christopher Lawson

Viscri church

FORTIFIED CHURCH IN TRANSYLVANIA

Lodgings

For bats

Hanging

Unauthorized

Like open umbrellas

In the armpits of walls.

When tourists come by

They crochet

Their legends,

Laughing softly,

With pigeon manure.

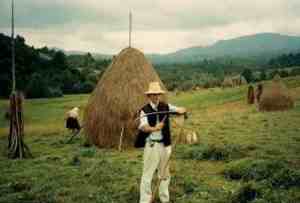

Transylvania, which I have known for almost 40 years, has one of the most stunning landscapes in Europe. Villagers live in handsome, colourful old homes on lanes lined with pear trees. Beyond their barns lie vegetable gardens, orchards and small farm plots. Farther out are meadows and pastures, carpeted with wildflowers, used cooperatively by the villagers for grazing animals and making hay. Imperious turkeys lead flocks of geese, ducks and chickens. Oak and beech woods cover the steep hillsides, where firewood is gathered.

In 1977, halfway through my teaching contract, Patrick Leigh Fermor, who died two years ago at the age of 96, published A time of gifts. In his trilogy, he depicts the Transylvania of the 1930s. The same year the notorious Madame Lupescu, widow of King Carol II, died in Estoril. Both events reminded me of another Romania and another time.

Following an invitation, I flew to Sibiu and was offered wine and tuica (plum brandy), with its wonderful golden colour, to accompany dinner. The following day, with friends, we walked into a valley and practiced FKK (nudity), just as Germans would in Germany. But here there was an element of protest against the highly puritanical Communist regime.

My hosts now live in Freiburg im Breisgau. Many of their former friends and neighbours from Sibiu live in the same city. Rroma (gypsies) have taken over the neat houses and orchards in Sibiu.

On another occasion, on a train journey, Adrian, an economist, invited me to stay in Sibiu, even though this was forbidden for foreigners. Shortly after our arrival at his apartment, his wife arrived, crying with triumphant laughter. Ceausescu had been to Sibiu on an official visit. The factories were closed and schoolchildren had the day off. They were supposed to line the streets, waving Romanian flags and cheering. But they had been directed to the wrong place. The streets were empty. There would be no pictures for the evening news.

Every week a group of friends gathered to watch Dallas. These young Romanians loved the beautiful women, the scheming menfolk, the huge cars and houses.

Sibiu now has a Saxon Mayor, Klaus Iohannis, who is re-elected with larger majorities by Hungarians and Romanians at each election. There are virtually no Saxons left. Iohannis has transformed Sibiu into a city which resembles one in Germany.

The spirit of Leigh Fermor infused the first Transylvania Book Festival, which took place in three Saxon villages from 5 to 9 September. Paddy was an exponent of leventeia, Greek for high spirits, humour, quickness of mind and action, the love of living dangerously and a readiness for anything. A handsome, bright-eyed teenager aged 18-19, Paddy had walked from the Hook of Holland to Istanbul, reciting verse as he walked, now staying in a hayrick, now in an aristocrat’s mansion. In wartime Crete, the dashing Paddy, Stanley Moss and a group of Cretan guerrillas abducted the German general commanding, drove him past 22 Nazi checkpoints, marched him through chilly mountains, and delivered him to Cairo.

Leigh Fermor was a great traveller and a sublime exponent of English prose.

Some 60 participants came to Richis, Copsa Mare and Biertan. The star of the show was Artemis Cooper, Paddy’s biographer. Her life of the great man, “An adventure”, is already a classic. She is also joint editor of “The broken road”, the long-awaited final book in his trilogy about his 1933-34 walk across Europe. Artemis sparkled. Another big name was Roy Foster, Professor of Irish Studies at Oxford, who spoke entertainingly on Bram Stoker and Dracula, first published in 1897 and never out of print since.

Jessica Douglas-Home, chairperson of the Mihai Eminescu Trust, one of the leaders of the fight to protect Transylvanian villages from Ceausescu’s lunatic systemization policy, was flanked by local Saxons, sundry poets and broadcasters, and the younger generation of burgeoning travel writers.

From the literary firmament came Beatrice Rezzori Monti della Corte, widow of Gregor von Rezzori, chronicler of Bukovina, and Elisabeth Jelen Salnikoff, grandaughter of Count Miklos Banffy who wrote a classic trilogy about the dying days of the Hungarian aristocracy. Presiding over this glitteringly impressive line-up was Lucy Abel Smith, an art historian resident in Transylvania several months of the year, who exuded energy, enthusiasm and good humour.

SHAKESPEARE

Shakespeare wrote about half of his late play Pericles (1608). His co-author, George Wilkins, a thoroughly disreputable and violent individual, a keeper of prostitutes, provided genuine inside knowledge of what went on in brothels which the fastidious Bard assimilated and made his own.

Shakespeare’s brothel scene takes place in Mytilene in Lesbos and contains the first reference to a Transylvanian in English, indeed in Western literature.

Pandar. Thou sayst true; they’re too unwholesome, o’ conscience. The poor Transylvanian is dead, that lay with the little baggage.

Boult. Ay, she quickly pooped him; she made him roast-meat for worms. But I’ll go search the market. [Exit]

Pandar, a procurer and pimp, discusses with Boult, his servant, the shortage of girls and how drab and diseased their prostitutes are. The “poor Transylvanian” has travelled to Greece to die of syphilis.

BROWNING

Much of Robert Browning’s familiar poem of 1842 about the Pied Piper of Hamelin is rooted in historical truth.

And I must not omit to say

That in Transylvania there’s a tribe

Of alien people who ascribe

The outlandish ways and dress

On which their neighbours lay such stress,

To their fathers and mothers having risen

Out of some subterraneous prison

Into which they were trepanned

Long time ago in a mighty band

Out of Hamelin town in Brunswick land,

But how or why, they don’t understand.

On 26 June, the Saints Day of John and Paul, in 1284, 130 of the town’s children in Hamelin (Hameln), Germany, totally disappeared. The town’s oldest record, dated 1384, states “It is 100 years since our children left.” A stained glass window (1300) in a Hamelin church which commemorated the event was destroyed in 1660.

King Geza II of Hungary (1141–1162) began the colonization of Transylvania in the mid-12th century to defend the southeastern border of his kingdom. A second phase came during the early 13th century. Saxons, as they were collectively known, were talented miners who could also develop the economy. The settlers came primarily from the Rhineland, the Southern Low Countries, Luxembourg and the Moselle region. To this day the Saxon dialect strongly resembles Letzebuergesch, the official language of Luxemburg.

Rats were not added to the story until 1599. Furthermore, the bubonic plague, the Black Death, did not reach Europe until 1348-1350.

The Saxons are an important element of Transylvania’s history. The vast majority of the Saxons have emigrated to Germany, but a few hundred still remain.

STOKER

Stoker wanted to call his novel Count Vampyr, or the Undead, when he discovered that the Romanian word Dracul meant Devil. He knew the legend of Vlad the Impaler from Wilkinson’s 1820 description of Wallachia and Moldavia. (But Wilkinson does not even use the name Vlad. He writes of Voivode Dracula.)

Vlad the Impaler was king on three separate occasions. He had acquired a fearsome reputation, but was also a defender of his territory against the Turkish invader. He ordered Turks and his Wallachian enemies to be skinned, boiled, decapitated, blinded, strangled, hanged, burned, roasted, hacked, nailed, buried alive, and stabbed. Impaling was his preferred method of execution.

Dracula scholars, notably Elizabeth Miller, argue that Stoker in fact knew little of the historic Vlad III except for the name “Dracula”. In Chapter 3, Dracula refers to his own background. Stoker directly copied parts of these speeches from Wilkinson’s book. Stoker’s gloomy, threatening Transylvania comes from books. The Irishman never travelled east of Vienna.

Stoker’s Dracula has many influences. Perhaps Dracula owes his existence to Celtic rather than Balkan sources. Stoker was born in the worst year of the great Irish famine and, although he lived most of his adullt life in England, he was steeped in Irish

mythology. Bram Stoker was just as fascinated by folklore and customs from his own country and other lands as well as those of Eastern Europe. Stoker was going to set his novel in Styria (Steiermark) when his attention was drawn to Transylvania.

Since the coup d’etat of 1989, there has been a marked increase in the number of books devoted to Romania and Transylvania. Of books published in the 20th century the most entertaining is Raggle-Taggle: Adventures with a Fiddle in Hungary and Roumania (1933) by that modern George Borrow, Walter Starkie, and the most exhilarating is Paddy’s Between the Woods and the Water.

I may be something of a romantic, but it is broadly true that, in Transylvania, Romanians, Hungarians, Saxons, Armenians, Jews and roma have been living peacefully with each other for centuries, a model for the rest of Europe.

Lucy Abel-Smith and Bronwyn Riley have commenced bookings for the 5th Transylvanian Book Festival to be helf in beautiful Richis in Transylvania over the period 12-15 September 2024. There is also an optional extension to visit the unique painted monasteries of Moldavia.

Lucy Abel-Smith and Bronwyn Riley have commenced bookings for the 5th Transylvanian Book Festival to be helf in beautiful Richis in Transylvania over the period 12-15 September 2024. There is also an optional extension to visit the unique painted monasteries of Moldavia.