A comprehensive profile of Patrick Leigh Fermor.

By James Campbell. First published in The Guardian 9 April 2005

As a teenager, Patrick Leigh Fermor walked through Europe to Turkey, sleeping in hayricks and castles. Forty years later he wrote two pioneering books about it; a third is still in progress. He lived in Romania, met his wife in Egypt, and was decorated for his wartime exploits in Crete. Now 90, he continues to work in the house he built in Greece in the 1960s.

“So here’s the traveller,” a Hungarian hostess greets the teenage Patrick Leigh Fermor as he trudges towards her Danubian country house. The year is 1934 and Leigh Fermor is four months into his walk from the Hook of Holland to Constantinople, undertaken to shake off what he refers to, 70 years on, as “my rather rackety past”. The journey is captured, with erudition and fond detail, in A Time of Gifts (1977) and Between the Woods and the Water (1986). They are unique in several respects, not least that they were written more than 40 years after the events described. Leigh Fermor derived the former title from a couplet by Louis MacNeice, “For now the time of gifts is gone – / O boys that grow, O snows that melt”, which encapsulates the double vision involved in evoking one’s own adolescence from a distance. A concluding volume, which will take the boy to his destination, has long been promised.

“So here’s the traveller,” a Hungarian hostess greets the teenage Patrick Leigh Fermor as he trudges towards her Danubian country house. The year is 1934 and Leigh Fermor is four months into his walk from the Hook of Holland to Constantinople, undertaken to shake off what he refers to, 70 years on, as “my rather rackety past”. The journey is captured, with erudition and fond detail, in A Time of Gifts (1977) and Between the Woods and the Water (1986). They are unique in several respects, not least that they were written more than 40 years after the events described. Leigh Fermor derived the former title from a couplet by Louis MacNeice, “For now the time of gifts is gone – / O boys that grow, O snows that melt”, which encapsulates the double vision involved in evoking one’s own adolescence from a distance. A concluding volume, which will take the boy to his destination, has long been promised.

Leigh Fermor is not a “travel writer” – like others, he disavows the term – but there is no denying he is a traveller. After Constantinople (as he still insists on calling it, though the name was changed to Istanbul in 1930), he moved to Romania, where he stayed for two years, barely conscious of the inklings of war from beyond the Carpathian mountains. In the 1950s, he explored the then-intractable southern finger of the Peloponnese known as Mani, where he lives, followed by a similar journey in the north of Greece, making his reports, in characteristically exuberant style, in the books Mani (1958) and Roumeli (1966). His stays in French monasteries, where he achieved “a state of peace that is unthought of in the ordinary world”, are recorded in an exquisite book of fewer than 100 pages, A Time to Keep Silence (1957).

Mani: Travels in the Southern Peloponnese

He is also a scholar, with a facility for languages so prodigious that he would amuse himself on his footslog by singing German songs backwards and, when those ran out, reciting parts of Keats the same way: “Yawa! Yawa! rof I lliw ylf ot eeht”, etc. “It can be quite effective,” he says. After a lunch of lemon chicken at home in Mani, accompanied by an endlessly replenished carafe of retsina, he entertains his guest with a rendering of “It’s a Long Way to Tipperary” in Hindustani.

In addition, Leigh Fermor is recognisably that figure many writers of the past century have yearned to be, the man of action. When the inklings could no longer be ignored in 1939, he abandoned his Romanian idyll and enlisted in the Irish Guards. A major in Special Operations Executive during the second world war, he was awarded the DSO for heroic actions on German-occupied Crete. Few writers are entitled to include in their Who’s Who entry: “Commanded some minor guerrilla operations.” His publisher, John Murray, whose father, the late “Jock” Murray, edited most of Leigh Fermor’s books, describes him as “almost a Byronic figure. If you met him on a train, before long he would be reciting The Odyssey , or singing Cretan songs. He loves talking, and people are always absorbed by him.”

Known as Paddy to the acquainted and unacquainted alike, Leigh Fermor has turned 90. He is still sturdy, with an all-round handsome appearance. Here is a man who at 69 swam the Hellespont (or Dardanelles), two kilometres wide at its narrowest, in emulation of Byron and Leander, who swam it nightly for the love of Hero. Leigh Fermor swam it under the concerned watch of his wife Joan, who followed in a small boat, and averted her eyes as he narrowly missed being sunk by a liner. An innocent sweetness hovers about his face, which finds a focus in his eyes as he makes a joke or stumbles on a happy recollection. There is a dash of the old soldier, clubbable and courteous, in his approach, his speech punctuated by “Look here …” and “I say …”, and not much of the “rather rackety” figure he claims to have been before he cured his ills by walking. When, relatively late in life, he became a mentor to Bruce Chatwin, the younger writer adopted Leigh Fermor’s motto, solvitur ambulando – it is solved by walking.

Paddy at home in the Mani

After more than six decades in the country, Leigh Fermor is inextricably tied to Greece. His command of the language extends to several regional dialects. He is an honorary citizen of the Cretan capital Heraklion, and of the village of Kardamili in Mani, and is a proud godfather to children in both places. In the mid-1960s, as if to lay the foundation for a committed life, he built a house that reflects the various aspects of his personality. Perched on a peninsula jutting into the Gulf of Messenia, it overlooks a small uninhabited island, behind which the sun sets nightly. He has described how he and Joan camped in tents nearby as the works progressed, studying Vitruvius and Palladio, but admits that the design was largely the result of improvisation. Ceilings, cornices and fireplaces allude to Levantine and Macedonian architecture. Hard by the commodious living room, an L-shaped arcade, which might have been built centuries ago, provides a link to the other rooms and gives on to an olive grove below. Out of nowhere, cats materialise on chairs and divans, prompting Leigh Fermor to remark on “interior desecrators and natural downholsterers”. The great limestone blocks of the main structure were hewn out of the Taygetus mountains, visible in the background, as the sea is present in the foreground. A weathered zigzag stone staircase leads down to a horseshoe bay. “There was no road here at all when we came. The stone had to be brought up by mule. We got most of the tiles from another part of the Peloponnese, after an earthquake. They were happy to be rid of them – couldn’t understand why we wanted this old stuff. They wanted everything new.” The master mason behind the house was a local craftsman, Niku Kolokatrones, whom Leigh Fermor met by accident while out walking. “I spotted his bag of carpenter’s tools and told him I was looking for somebody to help me build a house. He said, ‘Why not take me? I can do everything.’ And he was absolutely right.”

It was finally fit for habitation in 1968, and the couple “lived very happily here for 30 years”. Joan Leigh Fermor, daughter of the Conservative politician and First Lord of the Admiralty in Ramsay MacDonald’s coalition government, Bolton Eyres Monsell, died in 2003 at 91, after a fall. The couple met in wartime Cairo. She took the photographs for several of his books, including the first, The Traveller’s Tree (1950), an account of a journey through the West Indies, and for Mani and Roumeli – although these pictures have sadly been omitted from later editions.

He was born in London in 1915, to Sir Lewis Leigh Fermor, who became director-general of the Geological Survey in India, and Eileen Ambler, who was partly raised there. His childhood relationship with his parents was “rather strange, because I didn’t really know either of them until I was about three-and-a-half. My mother returned to India after I was born, leaving me with a family in Northamptonshire. I spent a very happy first three years of my life there as a wild-natured boy. I wasn’t ever told not to do anything.” When his mother returned, at the end of the first world war, “my whole background changed. We went to live in London. And she was rather unhappy, because I didn’t really know much about her, or my father or my sister, who had been born four years earlier. They hadn’t seen me since I was a few months old.” He claims he was “more or less tamed after that”, though he has written that his lawless infancy “unfitted me for the faintest shadow of constraint”.

Patrick Leigh Fermor at school, Kings� Canterbury

His mother “adored anything to do with the stage” and wrote plays that were never produced. She made friends with Arthur Rackham, who painted a picture inside the front door of their house in Primrose Hill Studios “of Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens, being blown along in a nest with a ragged shirt for a sail”. He wonders if it’s still there. When the time came to think about school, the “wild boy” re-emerged, and he was beaten from one educational establishment to another. “I didn’t mind the beatings, because there was a bravado about that kind of thing.” At one stage, he was sent to a school in Suffolk for disturbed children – or, as he puts it, “where rather naughty children went” – and later to King’s School, Canterbury, the oldest public school in England, where the unruly old boys included Christopher Marlowe. “It was all rather marvellous,” says Leigh Fermor, who casts a rosy light on almost all experience, “but my discipline problems cropped up again. Things like fighting, climbing out at night, losing my books.” Among his contemporaries at King’s was Alan Watts, who later wrote popular books on Zen Buddhism and became a hippie guru. In his autobiography, Watts recalled Paddy “constantly being flogged for his pranks and exploits – in other words, for having a creative imagination”. Watts confirms the familiar tale that Paddy was expelled “for the peccadillo of taking a walk with the daughter of the local greengrocer”. Leigh Fermor recalls: “She was about eight years older than me – totally innocent, but it was a useful pretext for the sack. I think it was very kindly meant. Far better to get the sack for something slightly romantic than for just being a total nuisance.”

Believing that the best place for a nuisance was the army, his parents tried to direct him towards Sandhurst, but his academic failures put paid to that too. The military historian Antony Beevor, who was an officer cadet at Sandhurst, and has known Leigh Fermor for many years, believes he would not have prospered. “I think he may have had a romantic idea of what army life was like, but he would have found the peacetime garrison incredibly stultifying. Army life in the 1930s was very staid. Paddy was too much of a free spirit.”

It was then that Leigh Fermor came up with a scheme “to change scenery”. Envisaging himself as “a medieval pilgrim, an affable tramp with a knapsack and hobnailed boots”, he decided to walk across Europe to Turkey. “It was a new life. Freedom. Something to write about.” To make it even more improbable, he set out in December when, as he states in the opening paragraph of A Time of Gifts, “a thousand glistening umbrellas were tilted over a thousand bowler hats in Piccadilly; the Jermyn Street shops, distorted by stream ing water, had become a submarine arcade.” When his ship docked in Rotterdam, “snow covered everything”. He dossed down wherever he landed, on one occasion outside a pigsty to the sound of “sleepy grunts prompted by dreams, perhaps, or indigestion”.

In addition to his sleeping bag, Leigh Fermor packed the Oxford Book of English Verse and a volume of Horace. An allowance of £4 a month was to be collected along the way. “My general course was up the Rhine and down the Danube. Then to Swabia, and then into Bavaria.” At the time, he had published a few poems (“dreadful stuff”), but was inspired to switch to travel writing by Robert Byron, whose book about a journey to Mount Athos in north-eastern Greece, The Station , had recently been published. “I was keeping copious notes, songs, sketches and so on, but in Munich a disaster happened. I stayed at a Jugendherberge and my rucksack was pinched, with all my notes and drawings.” And then comes the Paddy stroke: “In a way it was rather a blessing, because my rucksack was far too heavy. It had far too many things.” His sleeping bag was lost too -“good riddance, really” – and his money and passport. “The British Consul gave me a fiver – said pay me back some time.”

Leigh Fermor has pursued his literary career haphazardly. His Caribbean book was originally meant to be a series of captions for photographs. Then came his only novel, The Violins of Saint-Jacques (1953), followed by A Time to Keep Silence and Mani , all written in the mid-50s, after which he restricted himself to one public outing per decade. However, the 40-year interlude between the events of his European journey and the writing of the books enhances their appeal. At times, the hero of A Time of Gifts seems like a boy faced with a tapestry on which the entire history and culture of Europe is portrayed, unpicking it thread by thread. Byzantine plainsong; Yiddish syntax; the whereabouts of the coast of Bohemia (it existed, for 13 years); the finer nuances of regional architecture – “the wild scholarly enthusiasms of a brilliant autodidact”, as the writer William Dalrymple says. Theories are worked out, set down and often jettisoned, before another day’s walking begins. No one modulates as energetically from speculations on the origin of Greek place names to the “not always harmful effects of hangovers” as Leigh Fermor does. “If they fall short of the double vision which turns Salisbury Cathedral into Cologne,” he writes of his sore heads, “they invest the scenery with a lustre which is unknown to total abstainers.” When it came to writing about the journey, Leigh Fermor claims that “losing the notebook didn’t really seem to matter. I’d got all the places I’d been to noted down in another little notebook. Early impressions and all that sort of thing would only have been a hindrance.” It is impossible to say where imagination gets the upper hand over memory, and aficionados are adamant it does not matter.

Dalrymple, who as a student set out to follow the route of the First Crusade in emulation of Leigh Fermor, says: “I can’t think of any younger writers who have tried to write like Paddy, who have succeeded in the attempt. Not that I haven’t tried. When I set out on my first long journey in the summer vacation I had just read A Time of Gifts and I tried to write my logbook in faux-Paddy style. The result was disastrous. Just last summer I visited Mani and reread his wonderful book, and found myself again trying to write like him. I should have learned my lesson by now.” Dalrymple feels that the strongest influence of Leigh Fermor on the younger generation of travel writers “has been the persona he creates of the bookish wanderer: the footloose scholar in the wilds, scrambling through the mountains, a knapsack full of good books on his shoulder. You see this filtering through in the writing of Chatwin and Philip Marsden, among others.”

According to Jeremy Lewis, author of a biography of Cyril Connolly, with whom Joan was friendly, “Occasionally, one comes across some unromantic soul who objects to Leigh Fermor on the prosaic ground that he couldn’t possibly remember in such persuasive detail the events of 60 years ago.” Lewis suspects that “quite a lot of it is made up. He’s a tremendous yarn-spinner, and he has that slight chip on the shoulder of someone who hasn’t been to university. Sometimes one gets the feeling that he’s desperate to show he’s not an intellectual hick. He’s quite similar to Chatwin in that way. With Chatwin I find it irritating, but not with Leigh Fermor.” Lewis adds, “There is also a strong boy-scout element about him, which annoys some people, singing round the campfire and so on. I doubt if there was ever anything very rackety about Paddy.”

Balasha Cantacuzene

He has been asked many times why the composition of the books was delayed for so long, and has finessed the reply to his characteristic self-effacement: “Laziness and timidity.” He had a shot at writing during his sojourn in Romania in the late 1930s, “but I thought it was no good, so I shoved it aside. And I was right, actually, because when I tried it much later it all began to flow.” His companion in Romania, the first love of his life, was a young painter, Balasha Cantacuzene, whose family was part of an “old-fashioned, French-speaking, Tolstoyan, land-owning world. They were intensely civilised people. I spent the time reading a tremendous amount … when I wasn’t making a hash of writing. I felt rather different at the end of it all, from the kind of person I’d been before.”

After the communist takeover at the end of the war, the Ceausescu government branded the Cantacuzenes “elements of putrid background” and forced them to leave their property. Leigh Fermor made it his mission to rescue them from their new dismal circumstances, eventually succeeding in slipping into the country on a motorcycle and contacting Balasha and her sister. They met for only 48 hours. “We dared risk no more, and during that time I was unable to leave the tiny flat where they were then living, for fear of being seen.” He found that their early thoughts of leaving Romania had lapsed, “partly from feeling it was too late in the day; also, they said that Romania, after all, was where they belonged”.

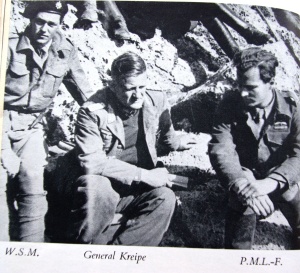

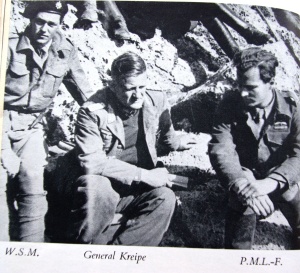

His war service was spent mainly on Crete. After the British retreat from the island in May 1941, Leigh Fermor was among a small number of officers who remained, helping to organise resistance to the occupation, “living up in the mountains, dressed as a shepherd, with my wireless and so on”. In the spring of 1944, after an onslaught on villages “with fire and sword” by German troops in reprisal for the rash actions of some Cretan guerrillas, Leigh Fermor conceived a plan to kidnap the general responsible for the carnage, and to spirit him off to Cairo. The idea was to make a “symbolic gesture, involving no bloodshed, not even a plane sabotaged or a petrol dump blown up; something which would hit the enemy hard”. Together with a select band of associates, British and Cretan, he succeeded – except that the officer they were after, General Müller, had already left Crete, and they found themselves taking charge of his replacement, a milder figure by all accounts, General Kreipe. After three weeks of trekking through the mountains, they managed to get the captive on board a vessel bound for Egypt.

The events were drawn into a book, Ill Met by Moonlight (1950), by Leigh Fermor’s comrade in the operation, W Stanley Moss, and an inferior film in 1957, with Dirk Bogarde playing Paddy. He is polite about the actor, whom he met, but it is clear that Bogarde’s performance as Major Fermor failed to impress. “I didn’t go to the opening, or anything like that. It was all so much more interesting than they made it seem.” The military historian MRD Foot has referred to the Cretan escapade as “a tremendous jape”, which in Leigh Fermor’s opinion puts it in a “rather frivolous perspective”. Beevor, whose book The Battle for Crete (1991), pays handsome tribute to Leigh Fermor’s actions, feels the description of the kidnapping as a “jape” is unjust. “What was very clever about the Kreipe operation was that it was planned meticulously to give the Cretans a tremendous boost to morale. They needed to do something that would damage the Germans, but was not going to provoke civilian casualties. They were absolutely scrupulous about this.” Certain accounts of the exploit have suggested that it resulted in reprisals against the local pop ulation, but, says Beevor, “they are completely wrong. I’ve been through all the relevant documentation, and there is nothing to suggest that the kidnapping of General Kreipe provoked direct reaction from the Germans. It wasn’t just a jape. When I was researching my book, a member of the Cretan resistance told me, ‘The whole island felt two inches taller’.”

Captor and captive, stuck together in freezing caves (the general had to sleep between Leigh Fermor and Moss, all sharing a single blanket), found a common bond in the Odes of Horace. In a report written at the request of the Imperial War Museum in 1969, published in Artemis Cooper’s anthology of Leigh Fermor’s writings, Words of Mercury (2003), he described what happened: “We were all three lying smoking in silence, when the general, half to himself, slowly said: ‘Vides ut alta stet nive candidum / Soracte …’ [You see how Soracte stands gleaming white with deep snow]. I was in luck. It is the opening line of one of the few Odes of Horace I know by heart. I went on reciting where he had broken off: ‘… Nec iam sustineant onus …’ and so on, through the remaining five stanzas to the end.”

Moss, Kreipe and Paddy

The heroics in eastern Crete had a surprise sequel, which throws into relief the absurdity of war. Some 30 years later, Leigh Fermor was asked to take part in a Greek television programme based on This Is Your Life , in which the subject was to be General Kreipe. “I felt quite certain when I heard about it that it was not on the level, and so I found out General Kreipe’s number and got on the telephone to him. I said, ‘It’s Major Fermor’. He said, ‘Ach, Major Fermor, how are you? It seems we are going to meet again soon.’ I said, ‘So you are coming?’ He said, ‘Yes, of course I’m coming. Tell me, what’s the weather like? Shall I bring a pullover?’ And you know, it was the most terrific success. They were all there.” The exception was Moss, who died in 1965; and it is probably safe to discount the Cretan guerrillas who carried off the general’s chauffeur and slit his throat, much to Leigh Fermor’s displeasure.

He writes in a small studio apart from the main house. Dictionaries, volumes of Proust, books of verse in various languages and back issues of the TLS occupy every surface. Asked if he has a title in mind for the promised last volume of his European trilogy, he looks suddenly pained and answers no. He describes himself as “a very slow writer”. His pages are laboriously revised and readers who revel in his florescent style may be surprised to learn that the finished sentences are pared down from something the author considers “too exaggerated and flowery and overwritten”. Murray says: “It’s rather like a musician: each time he changes a word, he has to go back and change all the other words round about it so that the harmony is right.” Murray recalls “seven versions of A Time of Gifts being submitted to my father. And each one would be written-over, with bubbles containing extra bits. The early manuscripts are like works of art themselves.”

As he is writing, Leigh Fermor thinks of one or two friends “that it might amuse. How would they respond? Where would they sneer?” He refers to his old notebooks for things like dates and place names, but relies on memory for a clearer vision of the walking boy and the snows. “I’ve written quite a large amount. For some reason, I got a sort of scunner against it several years ago. I thought it wasn’t any good. I always think that. But now I think I was wrong. I’m going to pull my socks up and get on with it.”

Patrick Leigh Fermor

Born: February 11, 1915, London.

Education: 1929-33 King’s School, Canterbury.

Married: 1968 Joan Eyres Monsell.

Employment: 1945-46 deputy director British Institute, Athens.

Books: 1950 The Traveller’s Tree; ’53 The Violins of Saint-Jacques; ’57 A Time To Keep Silence; ’58 Mani; ’66 Roumeli; ’77 A Time of Gifts; ’86 Between the Woods and the Water; ’91 Three Letters from the Andes; 2003 Words of Mercury.

Some awards: 1944 DS0; ’47 honorary citizen of Heraklion, Crete; ’58 Duff Cooper Memorial Prize; ’78 WH Smith Award; ’86 Thomas Cook Travel Book Award; ’91 Companion of Literature; 2004 Knighthood.