Paddy at the house in Kardamyli. Photo by Joan Leigh Fermor, Courtesy the New York Review of Books

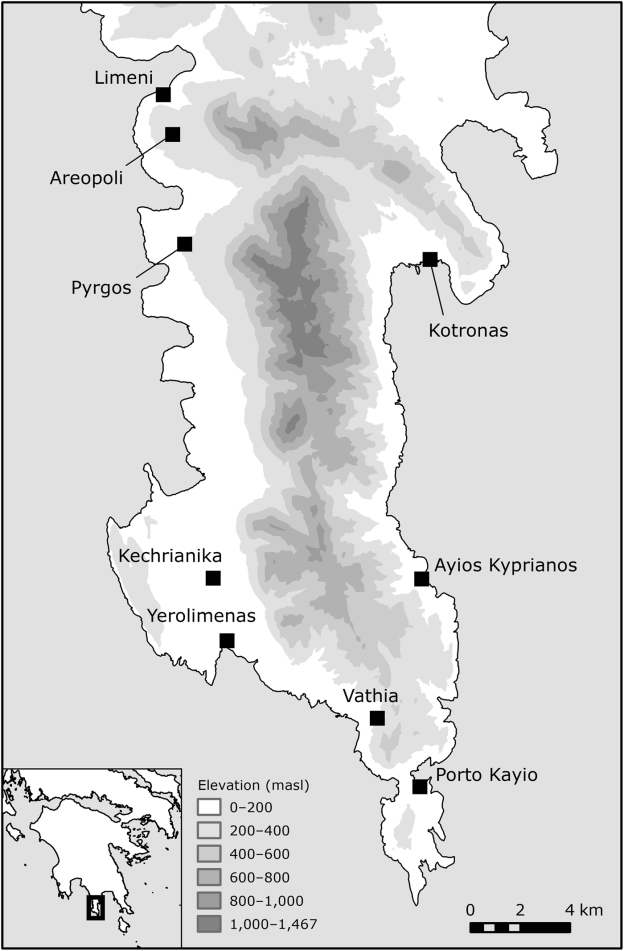

War hero, self-made scholar and the greatest travel writer of his generation, Patrick Leigh Fermor lived on a remote peninsula in the Peloponnese until his death in 2011. From a humble house he built himself, now being restored by an Athens museum, he explored Greece’s romantic landscape—and forged a profound link to its premodern past.

by Lawrence Osborne

First published in the Wall Street Journal Magazine 27 September 2012.

A famous anecdote, told by Patrick Leigh Fermor himself in his book Mani, relates how on one furnace-hot evening in the town of Kalamata, in the remote region for which that book is named, Fermor and his dinner companions picked up their table and carried it nonchalantly and fully dressed into the sea. It is a few years after World War II, and the English are still an exotic rarity in this part of Greece. There they sit until the waiter arrives with a plate of grilled fish, looks down at the displaced table and calmly—with an unflappable Greek stoicism—wades into the water to serve dinner. Soon the diners are surrounded by little boats and out come the bouzouki and the wine. A typical Fermor evening has been consummated, though driving through Kalamata today one has trouble imagining the scene being repeated. The somniferous hamlet of the far-off 1950s is now filled with cocktail bars and volleyball nets. The ’50s, let alone the war, seems like another millennium.

Fermor, or “Paddy,” as many educated Greeks knew him, died last year at the age of 96. He is remembered not only as the greatest travel writer of his generation, or even his century, but as a hero of the Battle of Crete, in which he served as a commando in the British special forces.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

“For as long as he is read and remembered,” Christopher Hitchens wrote upon Fermor’s death, “the ideal of the hero will be a real one.” Hitchens placed Fermor at the center of a brilliant English generation of “scholar warriors,” men forged on the battlefields of the mid-century: This included poet John Cornford, martyred in the Spanish Civil War, and the scholar and writer Xan Fielding, a close personal friend of Fermor’s who was also active in Crete and Egypt during the war, and a guest of the aforementioned dinner party. When Fermor said Fielding was “a gifted, many-sided, courageous and romantic figure, at the same time civilized and bohemian,” he could have been describing himself.

But Fermor was a man apart. Born in 1915 into the Anglo-Irish upper class—the son of a famous geologist—Fermor, literally, walked away from his social class and its expectations almost at once. At 18, he traveled by foot across Europe to Constantinople—a feat later recorded in his books A Time of Gifts and Between the Woods and the Water. In the ’30s he traveled through Greece, mastering its language and exploring its landscapes with meticulous attention. He fell in love with a Romanian noblewoman, Balasha Cantacuzene (a deliciously Byzantine name), and the outbreak of war found him at her family estate in Moldavia.

Because of his knowledge of Greek, the British posted him to Albania. He then joined the Special Operations Executive (SOE) and was subsequently parachuted into German-occupied Crete. In 1944 Fermor and a small group of Cretan partisans and British commandos kidnapped General Heinrich Kreipe, commander of the German forces on the island, and drove him in his staff car through enemy lines disguised in German uniforms. (They would have been shot on the spot if discovered.) Kreipe was later spirited away to British Egypt, but as they were crossing Mount Ida, a legendary scene unfolded. Fermor described it himself:

“Looking across the valley at [the] flashing mountain-crest, the general murmured to himself: ‘Vides ut alta stet nive candidum Soracte.’ [See how Mount Soracte stands out white with deep snow.] It was one of the [Horace odes] I knew! I continued from where he had broken off… The general’s blue eyes had swivelled away from the mountain-top to mine—and when I’d finished, after a long silence, he said: ‘Ach so, Herr Major!’ It was very strange. As though, for a long moment, the war had ceased to exist. We had both drunk at the same fountains long before; and things were different between us for the rest of our time together.”

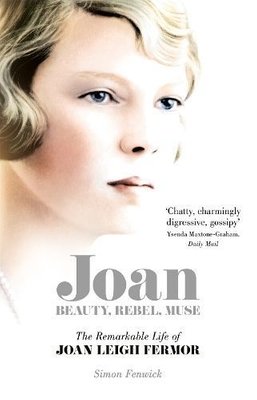

After the war, now decorated for his heroism, Fermor settled in Greece. He and his wife, Joan Rayner, a well-traveled Englishwoman whom he’d met in Cairo, built a house just outside the village of Kardamyli, a few miles down the jagged coast from Kalamata, in the wild and remote Mani. It was a place that, even in the early ’60s, almost no one visited. “Homer’s Greece,” as he put it admiringly.

“It was unlike any village I had seen in Greece,” he wrote in Mani. “These houses, resembling small castles built of golden stone with medieval-looking pepper-pot turrets, were topped by a fine church. The mountains rushed down almost to the water’s edge with, here and there among the whitewashed fishermen’s houses near the sea, great rustling groves of calamus reed ten feet high and all swaying together in the slightest whisper of wind.” It was timeless. Kardamyli, indeed, is one of the seven cities that Agamemnon offers a scowling Achilles as a reward for his rejoining the paralyzed Achaean army at Troy in The Iliad.

“Not a house in sight,” Fermor later wrote of his adopted view, in a letter to his friend the Duchess of Devonshire, “nothing but the two rocky headlands, an island a quarter of a mile out to sea with a ruined chapel, and a vast expanse of glittering water, over which you see the sun setting till its last gasp.”

The house, still largely untouched from when Fermor lived there, was bequeathed to the Benaki Museum in Athens. As I walked through it alone during a visit there this spring, it reminded me in some ways of Ian Fleming’s Goldeneye in Jamaica, a spartan but splendidly labyrinthine retreat devoted to both a productive life and to the elegant sunset cocktail hour. In one bedroom stood a set of Shakespeare volumes with painstakingly hand-penned spines; on a wall, a painted Buddhist mandala. In the living room there were faded wartime photographs of Fermor on horseback, armed and dressed like a Maniot. The whole house felt like a series of monastic cells, their piety replaced by a worldly curiosity, an endless warren of blackened fireplaces, bookshelves and windows framing the sea.

Fleming and Fermor were, perhaps predictably, close friends. Fleming’s Live and Let Die freely quotes from Fermor’s book about the Caribbean, The Traveller’s Tree. It was Fermor who made Fleming (and, of course, Bond) long for Jamaica. But where Fleming retreated to Jamaica to knock out six-week thrillers, Fermor lived in his landscape more deeply; he explored with dogged rigor its ethnography, its dialects, its mystical lore. His books are not “travel” in the usual sense. They are explorations of places known over years, fingered like venerable books and therefore loved with precision, with an amorous obsession for details.

Fermor led an active social life, and the house in Mani, however remote, was a place that attracted many friends, literary luminaries and even admiring strangers over the years. His circle included the historian John Julius Norwich and his daughter, Artemis Cooper; the literary critic Cyril Connolly; the Greek painter Nikos Ghika; and the writer Bruce Chatwin. In an obituary for Fermor in 2011, The New York Times put it thus: “The couple’s tables, in Mani and in Worcestershire, were reputed to be among the liveliest in Europe. Guests, both celebrities and local people, came to dine with them. The journalist and historian Max Hastings called Mr. Leigh Fermor ‘perhaps the most brilliant conversationalist of his time, wearing his literacy light as wings, brimming over with laughter.’ ”

Standing on Fermor’s terrace, with its fragments of classical sculpture and its vertiginous view of a turquoise cove of stones, I felt as if the inhabitants of 40 years ago had momentarily gone inside for a siesta and would soon be out for a dusk-lit gin and tonic. It seemed a place designed for small, intimate groups that could pitch their talk against a vast sea and an even vaster sky.

It also had something neat and punctilious about it. While sitting there, I could not help remembering that Fermor had once sternly corrected Fleming for a tiny factual error in his novel On Her Majesty’s Secret Service. Didn’t Fleming know that Bond could not possibly be drinking a half bottle of Pol Roger? It was the only champagne, Fermor scolded, never sold in half bottles. It was exactly the sort of false note that Paddy never missed, and that the creator of Bond should not have missed either. Truth for Fermor lay in the details, and his books show the same straining eye for the small fact, the telling minutiae.

I noticed, meanwhile, a handsomely stocked drinks cabinet inside the house, in the cool, cavernously whitewashed living room lined with books—the selection dominated by a fine bottle of Nonino grappa. On the mantelpiece stood a card with the telephone numbers of his closest friends, Artemis Cooper (whose biography of Fermor is being published this month) and Deborah Mitford, later the Duchess of Devonshire.

Fermor had been at the heart of many aristocratic circles, including those of the notorious Mitford sisters. The youngest of the Mitfords—”Debo,” as she was known—became Fermor’s lifelong intimate and correspondent. Their polished and witty letters have recently been published in the book In Tearing Haste.

He was a frequent visitor at her country estate, Chatsworth, and the two were platonically entwined through their letters well into old age. They were, however, strange epistolary bedfellows. The Duchess hated books (“Quelle dread surprise,” she writes upon learning that a famous French writer is coming to dinner), while Fermor was the very definition of the dashing, encyclopedic gypsy scholar. In one letter the Duchess boasts that Evelyn Waugh gave her a signed copy of his latest book, which turned out to have blank pages throughout; he knew she hated reading. But the gardening-mad Duchess slyly understood all her correspondent’s erudite gags.

Their gossip was gentle and civilized, and underneath it flowed a kind of unrequited love. In his first letter of the collection, written in 1955 from Nikos Ghika’s house on Hydra, Fermor proposes having himself turned into a fish by a young local witch and swimming all the way from Greece to Lismore Castle in Ireland, where the Duchess was staying.

“I’m told,” he writes, “there’s a stream that flows under your window, up which I propose to swim and, with a final effort, clear the sill and land on the carpet…But please be there. Otherwise there is all the risk of filleting, meunière, etc., and, worst of all, au bleu…”

The Mani, meanwhile, was a far cry from English country houses and fox-hunting parties. Its remoteness and austerity—especially immediately after the war—were truly forbidding. As Fermor pointed out, this was a place that the Renaissance and all its effects had never touched. It was still sunk in Europe’s premodern past—a place still connected by a thousand invisible threads to the pagan world.

Above Kardamyli rise the Taygetus range and the forests that Fermor loved to wander. Steep paved footpaths called kalderimi ascend up into half-abandoned villages like Petrovonni and, above it, the church of Agia Sophia, which looks down on the Viros Gorge. In Mani Fermor remembers that it was here, near the city of Mistra, that Byzantium died out a few years after the fall of Constantinople, and where the continuously creative Greek mind lasted the longest. It is a delicate, luminous landscape—at once pagan and Christian.

Fermor discovered that Maniots still carried within them the demonology of the ancient world, filled with pagan spirits. They called these spirits the daimonia, or ta’ xotika: supernatural beings “outside” the Church who still—as Nereids, centaurs, satyrs and Fates—lived in the streams and glades of the Mani. They still believed in “The Faraway One,” a spirit who haunted sun-blazing crossroads at midday and who Fermor deduced to be the god Pan. The Mani was only Christianized, after all, in the 10th century. Fermor also described how an illiterate Greek peasant, wandering through archaeological museums, might look up at ancient statues of centaurs and cry, immediately, “A Kallikantzaros [centaur]!” To him, it was a living creature.

I hiked up to Exohori, where Bruce Chatwin had, 25 years ago, discovered the tiny chapel of St. Nicholas while he was visiting Fermor. (I had, in fact, been given Chatwin’s old room in the hotel next to Fermor’s house.) Chatwin venerated the older writer, and the two men would walk together for hours in the hills. Fermor, for his part, found Chatwin enchanting and almost eerily energetic. Yet Chatwin was inspired not just by Fermor but by where he lived. When Chatwin was dying, he converted to Greek Orthodox. It was Fermor, in the end, who buried Chatwin’s ashes under an olive tree next to St. Nicholas, in sight of the sea of Nestor and Odysseus.

Exohori felt as deserted as the other strongholds of the Mani, its schools closed and only the elderly left behind. It possesses an atmosphere of ruin and aloofness. I remembered a haunting passage from Mani in which Fermor describes how villagers once scoured out the painted eyes of saints in church frescoes and sprinkled the crumbs into the drinks of girls whom they wanted to fall in love with them. So, one villager admits to Fermor that it wasn’t the Turks after all.

As a former guerrilla of the savage Cretan war, Fermor felt at home here. It was a thorny backwater similarly ruled by a warrior code. Its bellicose villages were, almost within living memory, frequently carpeted with bullet casings. It was a vendetta culture.

The Mani was for centuries the only place in Greece apart from the Ionians islands and Crete (which, nevertheless, fell to the Turks in 1669) to remain mostly detached from the Ottoman Empire. Its people—an impenetrable mix of ancient Lacedaemonians, Slavs and Latins—were never assimilated into Islamic rule, and their defiant palaces perched above the sea never had their double-headed Byzantine eagles removed. Here, Fermor wrote, was “a miraculous surviving glow of the radiance that gave life to this last comet as it shot glittering and sinking across the sunset sky of Byzantium.” Mani, therefore, explores wondrous connections in our forgotten Greek inheritance (it argues, for example, that Christianity itself was the last great invention of the classical Greek world). But Fermor’s philhellenism was not dryly bookish. It was intensely lived, filled with intoxication and carnal play.

His contemporary and fellow Anglo-Irish philhellene Lawrence Durrell was, in so many ways, his kindred spirit in this regard. They were also close friends and had reveled together at the famous Tara mansion in Cairo during the war. Mani, in any case, stands naturally beside Bitter Lemons and Prospero’s Cell as love songs to the Greece of that era. In Ian MacNiven’s biography of Durrell, we find an enchanting glimpse of a riotous Fermor visit to Durrell in Cyprus just after the war. The two men stayed up half the night singing obscure Greek songs, rejoicing in shared Hellenic lore and making a lot of noise.

“Once as they went through Paddy’s vast repertoire of Greek songs far into the night, the lane outside the house filled with quiet neighbors, among them the usually boisterous Frangos, who told Larry, ‘Never have I heard Englishmen singing Greek songs like this!’ ” Their shared virtuosity in the Greek language was remarkable.

Greece, for some of the young prewar generation, held a special magic. It was a youthful Eden, a place linked to the ancient world that was doomed to disappear in the near future. It’s a mood cannily incarnated in Henry Miller’s The Colossus of Maroussi, which records journeys that Miller and Durrell undertook together in 1939. But no one sang Greece more profoundly than Fermor, and no one tried more ardently to argue its core importance to Western culture, both now and—a more radical argument—in the future.

Roumeli and Mani are his twin love songs to Greece, but it is in Mani that he most eloquently lamented the disappearance of folk cultures under the mindless onslaught of modernity and celebrated most beautifully what he thought of as an immortal landscape in which human beings naturally found themselves humanized.

Consider his illustration of the Greek sky that always seemed to hang so transparently above his own house: “A sky which is higher and lighter and which surrounds one closer and stretches further into space than anywhere else in the world. It is neither daunting nor belittling but hospitable and welcoming to man and as much his element as the earth; as though a mere error in gravity pins him to the rocks or the ship’s deck and prevents him from being assumed into infinity.”