'A dangerous mixture of sophistication and recklessness': Patrick Leigh Fermor in Saint Malo, France, in 1992 Photograph: Ulf Andersen/Getty Images

Highly regarded travel writer and heroic wartime SOE officer

By James Campbell

First published in The Guardian 10 June 2011

Patrick Leigh Fermor, who has died aged 96, was an intrepid traveller, a heroic soldier and a writer with a unique prose style. His books, most of which were autobiographical, made surprisingly scant mention of his military exploits, drawing instead on remarkable geographical and scholarly explorations. To Paddy, as he was universally known, an acre of land in almost any corner of Europe was fertile ground for the study of language, history, song, dress, heraldry, military custom – anything to stimulate his momentous urge to speculate and extrapolate. If there is ever room for a patron saint of autodidacts, it has to be Paddy Leigh Fermor.

Rather than go to university in 1933, at the age of “18 and three-quarters”, he set out in December that year to walk from the Hook of Holland to what he insisted on calling Constantinople, or even Byzantium [Istanbul]. There was no hurry, he wrote 65 years later in an article for the London Magazine. His journey took him “south-east through the snow into Germany, then up the Rhine and eastwards down the Danube … in Hungary I borrowed a horse, then plunged into Transylvania; from Romania, on into Bulgaria”. At New Year, 1935, he crossed the Turkish border at Adrianople and reached his destination.

The European trek was undertaken with a book in mind – he was inspired by George Orwell’s Down and Out in Paris and London – but 40 years would pass before Paddy published the first volume of his projected trilogy on the adventure. Asked why it took so long, he shot back: “Laziness and timidity.” A Time of Gifts (1977) is not only a great travel book (a term he disliked), but one of the wonders of modern literature.

Five years after his journey ended, he was serving with the Irish Guards during the second world war. He joined the Special Operations Executive in 1941, helping to co-ordinate the resistance in German-occupied Crete, and commanding, as he put it, “some minor guerrilla operations”. The most audacious was the ambush and kidnap of the man overseeing the Nazi occupation of the island, General Heinrich Kreipe, who was spirited off to Alexandria.

Paddy’s adventures began practically at the moment he was born. His father, Sir Lewis Leigh Fermor, was the director of the Geological Survey of India. After giving birth to her son in London, his mother, Eileen (nee Ambler), a hopeful but unsuccessful playwright, took Paddy’s elder sister and returned to the east. The newborn was left behind, “so that one of us might survive if the ship were sunk by a submarine”. He was raised in Northamptonshire by a family called Martin and, as he told me when I interviewed him in 2005, “spent a very happy first few years of my life as a wild-natured boy. I wasn’t ever told not to do anything.” The experience left him unsuited to “the faintest shadow of constraint”. As for his parents, “I didn’t meet either of them until I was four years old”. Lewis and Eileen later separated, and Paddy then lived with his mother in London, near Regent’s Park.

With pride, he would tell how he went to a school “for rather naughty children”, and was expelled from two others, including the King’s school, Canterbury, where he had formed an illicit liaison with the local greengrocer’s daughter, eight years older than him, in whom perhaps he glimpsed a loving mother. His housemaster described him as “a dangerous mixture of sophistication and recklessness”, which was perceptive.

Among the books he packed for his European journey in 1933 was a volume of Horace. To pass the time while marching, he recited aloud “a great deal of Shakespeare, several Marlowe speeches, most of Keats’s Odes” as well as “the usual pieces of Tennyson, Browning and Coleridge”. This would be related with charming if showy modesty.

The immense repertoire had a frivolous side. Throughout his adult life, Paddy was a great performer of party turns: songs in Cretan dialect; The Walrus and the Carpenter recited backwards; Falling in Love Again sung in the same direction – but in German. When I was at his house in the Peloponnese, in Greece, he restricted himself, after a lunch that lasted several hours, to It’s a Long Way to Tipperary in Hindustani.

A Time of Gifts is written with a youthful eagerness, with intricately detailed descriptions of sights passed along the way, conversations, drinks imbibed, the cadence of birdsong. Yet it is almost entirely a work of mature recollection. The figure setting out for the Netherlands after a final celebration with friends – “a thousand glistening umbrellas were tilted over a thousand bowler hats in Piccadilly; the Jermyn Street shops, distorted by streaming water, had become a submarine arcade” – is a lad of 18, with all the appropriate responses, but his sensibility is in the control of a writer several decades older. While making a BBC television programme about Paddy’s journey in 2008, the explorer and film-maker Benedict Allen was able to authenticate many of the elaborate and seemingly fanciful descriptions in the book.

Back in Athens, after the main journey to Istanbul was completed, Paddy met the first great love of his life, Balasha Cantacuzene, a Romanian princess 12 years his senior, with whom he lived on the family’s “Tolstoyan” estate in Moldavia until the outbreak of the war. A quarter of a century later, he returned to Romania and found the princess living in a Bucharest garret, disgraced by the government, but with charm and humour intact.

In the 1950s, he lived the life of a nomad. His letters to the Duchess of Devonshire (their correspondence was published as In Tearing Haste in 2008) carry addresses in Italy, France, Cameroon, as well as various corners of England and his beloved Greece. He had a lifelong attraction to the aristocracy, and it sometimes seems as if every excursion involved a castle or a palace somewhere, and every other acquaintance had a title, but his charm and popularity resided in the fact that he was just as content dancing with Greek peasants and sleeping under stars.

Elaboration was Paddy’s forte. His manuscripts were like some literary version of snakes and ladders, with the revisions themselves undergoing repeated rewriting. A friend told me that even quotations from other authors were subject to revision. The second volume, Between the Woods and the Water, appeared in 1986, taking the traveller up to Orsova on the Danube south of the Carpathians. The final chapter closes with the hopeful words, “To Be Concluded”. All through his 80s and 90s, well-meaning friends and fans alike asked about the progress of volume three, and Paddy, hiding his irritation, would say that he was “going to pull my socks up and get on with it”. A visitor to his Greek home in 2008 saw an eight-inch-high pile of manuscript. When and if it does appear, this will be a series some eight decades in the making.

Paddy was never to match the productivity he achieved during the 50s. His first book was The Traveller’s Tree (1950), based on a voyage in the Caribbean in the company of Joan Eyres-Monsell, daughter of the First Lord of the Admiralty, whom he had met at the end of the war. Paddy and Joan became lifelong companions (they married in 1968). She had “more money than most of her friends”, an old school chum wrote at Joan’s death in 2003, aged 91. They settled in Greece in 1964 (three year before the colonels’ junta), while keeping a house near Evesham, in Worcestershire.

After The Traveller’s Tree came his only novel, The Violins of Saint-Jacques (1953), also with a Caribbean setting (it was made into an opera by Malcolm Williamson). Lodging at a Benedictine monastery in Normandy in the mid-50s in order to concentrate on the first of his two books about Greece, he ended up writing about the monastery instead. A Time to Keep Silence (1957) is the least elaborate and most accessible of his books. It included photographs by Joan, as did Mani (1958), a compendious account of the southernmost region of the Peloponnese. Its northern Greek twin, Roumeli, appeared in 1966. Other notable projects included translations from the French of Paul Morand and co-writing the screenplay for John Huston’s film The Roots of Heaven (1958).

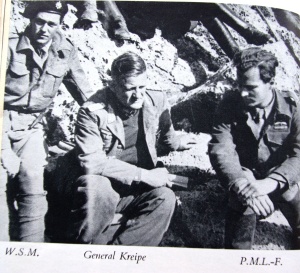

He took no part in the making of the film with which most people associate him. Ill Met by Moonlight (1957) is Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s rather feeble version of the kidnap of General Kreipe. Dirk Bogarde played Paddy, who disliked the film. “It was all so much more interesting than they made it seem,” he told me.

The kidnap took place in April 1944. With permission from the Special Operations Executive (SOE) in Cairo, Paddy and his team of British commandos and Cretan guerrillas stopped Kreipe’s car as made its way to HQ in Heraklion. With the general pressed down on the vehicle’s floor, Paddy donned his uniform and set off towards a prearranged hiding-place with the captive on board. The German chauffeur had been carried off and killed by the Cretans, much to the displeasure of Paddy, who had wanted to keep the operation bloodless in order to reduce the chance of reprisals.

Before reaching safety, they had to pass through several roadblocks and were saved only by Paddy’s command of German. The strange company – Paddy, the general and W Stanley Moss (author of the book Ill Met by Moonlight) slept in caves for a month until it was safe to have Kreipe removed to Egypt. Passing the time one day, Kreipe began to recite some lines from Horace’s ode Ad Thalictrum. The Latin syllables caught his captor’s ear. “As luck would have it, it was one of those I knew by heart.” After the general had run out of steam, Paddy carried on through the remaining 40 lines to the end. “We got on rather better after that.” In 1972, an almost equally unlikely event occurred, when the pair were reunited on a Greek version of This Is Your Life.

Until his death, Paddy was pursued by the rumour that his “jape” (as the historian MRD Foot called it) had brought terrible vengeance on the local population. In a Guardian obituary in 2006 of George Psychoundakis, a shepherd and a “runner” in the resistance, it was stated that villages had been burned in reprisal for the Kreipe kidnapping. This was denied and later corrected by the newspaper. In his book Crete: The Battle and the Resistance (1991), Antony Beevor went to some lengths to establish with the help of German documentation that no direct reprisals took place. Certainly, the Cretans were grateful to Paddy and the odd bunch of English classicists and scholars – some of them posted to Crete on account of having studied ancient Greek at school – who were among his colleagues. In 1947, he was made an honorary citizen of Heraklion. In the mid-50s, he translated Psychoundakis’s close-up version of the occupation, The Cretan Runner (1998), and was later responsible for having the shepherd’s vernacular rendering of the Odyssey published in Athens.

In 1964, the Leigh Fermors focused their energy on building a house on a peninsula about a mile outside the village of Kardamyli. A local mason, Nikos Kolokotronis, provided the expertise. “Settled in tents, we read Vitruvius and Palladio,” Paddy wrote. “Learned all we could from old Mani buildings, and planned the house.” Limestone was quarried from the foothills of the Taygetos mountains, which rear up behind the building as the Gulf of Messenia opens before it. Other materials, such as a seven-foot marble lintel, came from Tripoli and beyond.

He was justly proud of the garden (designed by Joan), the sundial table and the fabulous azure prospect below. There was nothing fussy about it. Paddy referred to his chair-scratching cats as “interior desecrators and natural downholsterers”, and enjoyed the day when “a white goat entered from the terrace, followed by six more in single file”. They inspected the living room, then left again “without the goats or the house seeming in any way out of countenance”.

It was from the same terrace that I first entered the living room, the only guest, apart from the goats, ever to have done so, according to Paddy. Staying in a pension in Kardamyli, I had loftily turned down the offer of a lift to our lunch appointment, and set out to walk with rudimentary directions. I was soon lost, scrambling down olive terraces, smearing and tearing my carefully pressed trousers. Worse, I was late. Eventually, I came to the sea and after climbing over rocks as large as a garden shed, arrived at a set of zigzag steps leading up the cliff face. I traipsed across the terrace and entered by the French windows, to find Paddy seated on a divan reading the Times Literary Supplement. He complimented me on my sense of direction, and said urgently: “We must have a drink straight away!” Paddy was a two gin-and-tonics before lunch man. He was, in fact, a promoter of the life-enhancing qualities of alcohol, and even of the “not always harmful” effects of a hangover.

In 1943, he was appointed OBE (military), and a year later received the Distinguished Service Order. His books won many awards, including the Duff Cooper memorial prize (for Mani) and the WH Smith award (A Time of Gifts). He was knighted in 2004.

Peter Levi writes: When Patrick Leigh Fermor announced his intention to walk to Constantinople through Bulgaria, he was warned by an old British sergeant with local experience that if he went that way, he would start out with a bum like silk and end up with one like an army boot. This view turned out to be mistaken, but among many other adventures, he played bicycle polo in Hungary, fell passionately in love with a princess in Romania, and took part in the last Greek cavalry charge, in a civil war he never quite understood.

He was exactly the right age to be a war hero, and in his two years with the Cretan resistance made a number of lifelong friends, blood-brothers and brothers by baptism. At one point General [later Field Marshal] Bernard Montgomery ordered him to depart at once and come on leave to Cairo, but received a telegram saying he had misunderstood, and that Major Leigh Fermor was enjoying himself enormously and did not want any leave. “What I liked about Paddy,” one of his Cretan blood-brothers said to me, “was he was such a good man, so morally good. He could throw his pistol 40 feet in the air like this, and catch it again by the handle.”

He was not meant for the boring side of military life. When he did get to Cairo. he learned the SOE song, to the tune of a popular song of the time. “We’re a poor lot of mugs/ Who were trained to be things,/ And now we’re at the mercy of the Greeks and the Jugs,/ Nobody’s using us now.” His Cairo parties were also memorable. It was the Indian summer of whatever Cairo had once been, and there was one party where he counted nine crowned heads among the guests. His way into this happy life was by volunteering for the Irish Guards, being put into the intelligence corps, and working as a liaison officer with the Greeks.

His way out was equally a matter of luck. After some time in airborne reconnaissance over Germany in 1945, he was made vice-director of the British Institute in Athens by Lieutenant General Ronald Scobie, who wanted courses in Greek culture and archaeology organised for his soldiers, who had nothing to do. One of his first recruits to the small corps of lecturers was the author and translator Philip Sherrard. They were both at the beginning of a long love affair with their subject.

Paddy came home to be demobbed, and lived for a time in the couriers’ rooms high up in the Ritz hotel that cost half a guinea a night. He arrived there with Xan Fielding, his comrade in arms, who had a barrel of Cretan wine on one shoulder, and with Joan.

He was so honestly high-spririted and friendly that many who were prepared to reject him fell at once under his charm. He was still as wild as he would have been at 16. He was the sort of man who would take you to White’s for dinner because you were handy, without telling you he was a new member, and proceed to sing the menu in Italian.

The house where he and Joan lived in Greece was as essential an expression of his creative power as Pope’s Twickenham or Horace Walpole’s Strawberry Hill. Its remarkable tranquillity and beauty were qualities seldom encountered. His writing house in the garden had a magnificent stove-like fireplace, an imitation from a prewar Bulgarian house, and the saloon or great room of their house had a huge window of Turkish inspiration. It was a feat that he stayed on intimately good terms with the Greeks for so many years. The only problem was about water rights: he supplied mountain water free, which was at once used as a basis for a new settlement with all the horrors of development to follow. When he cut off the supply there were growls, but peace soon returned.

He was a member of the Academy of Athens, and got a gold medal from the city authorities. His London life was dashing. Dressed for a night on the town in what he called his James Bond greatcoat, a present from Ian Fleming, he was a fine sight.

Among his casual attainments, he climbed a peak in the Andes with the mountaineer Robin Fedden and the Duke of Devonshire (who beat the others to the top), and he swam the Hellespont, where he encountered a Russian submarine. In the 1980s he underwent treatment for cancer, which proved successful. Yet his life was distinctly bookish and scholarly: he was a discoverer of obscure and new writers, he translated poetry, and was at some deep level essentially a poet.

• Patrick Michael Leigh Fermor, soldier, traveller and writer, born 11 February 1915; died 10 June 2011

• Peter Levi died in 2000