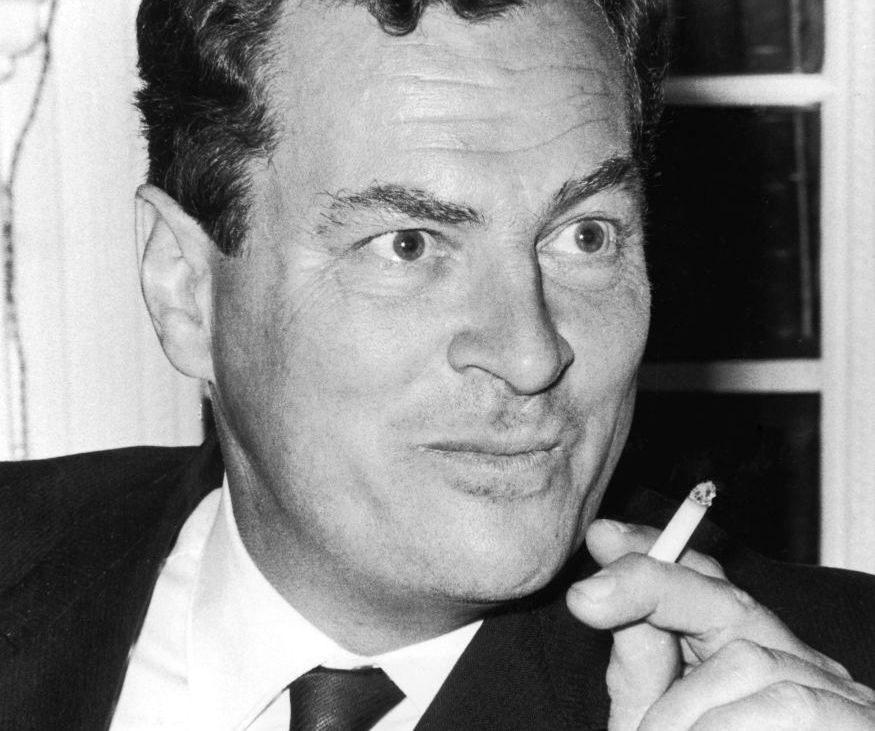

Patrick Leigh Fermor writing under a makeshift shelter in his garden at Kardamyli, Greece. Credit…Estate of Patrick Leigh Fermor

It has been a while since I posted a book review on here. Some more recent readers may wonder why I am posting a book review from 2017. One stated purpose of the blog is to bring all (suitable and relevant) material relating to Paddy under on roof, hence the reason for posting this good quality review by Charles McGrath of A Life in Letters by Adam Sisman (published in the UK 2016 as Dashing for the Post), published in the New York Review Books December 1 2017.

Though hardly known in this country, in his native England Patrick Leigh Fermor is practically a cult figure, often said to be the best travel writer of the 20th century. But Fermor — or Paddy, as he was known to just about everyone — was also a famous vacillator and procrastinator, always distractable, unable to meet a deadline, and much of the effort he might have put into books and articles went into letters instead. Adam Sisman, the editor of this volume, guesses that in the course of his very long life (Fermor died in 2011, at 96) he might have written as many as 10,000. Sisman has selected fewer than 200, but they do add up to a biography of sorts — or, rather, a scrapbook of a rich, fascinating life lived mostly out of a suitcase and in a race to the post office. Until he was almost 50, and finally owned a house, Fermor seldom stayed in one place longer than a month.

The Fermor who emerges in these letters (and in a conventional biography published in 2012 by Artemis Cooper, granddaughter of Lady Diana Cooper, one of his most favored correspondents) was a bundle of contradictions. He was a man of letters but also, like his hero Byron, a man of action — a war hero and a restless adventurer, who even swam the Hellespont when he was 69. He never finished school — his headmaster called him “a dangerous mixture of sophistication and recklessness” and tossed him out for holding hands with a shopkeeper’s daughter — but was prodigiously learned, conversant in at least eight languages and able to recite hours of poetry by heart. He was an old-school Englishman, a toff — bespoke clothes, club memberships, plummy accent, riding to hounds — who lived most of his life abroad, broke much of the time, settling down at last in Greece. He was an unabashed snob and social climber who also relished the company of peasants and shepherds. He was a famous ladies’ man and at the same time deeply in love with his wife, who patiently overlooked his wanderings. (She even lent him money for prostitutes.) And he was a tireless socializer, beloved by an enormous circle of friends, who often yearned for solitude and sometimes hid out in monasteries.

Fermor was, as he freely admitted, a shameless scrounger of invitations and of houses he could borrow. (Invited once for lunch at Somerset Maugham’s villa on Cap Ferrat, he reportedly showed up with five cabin trunks, intending to stay for weeks. Maugham dispatched him the next morning.) His letters were, among other things, a way of keeping up with his friends and repaying their hospitality. Many of them are not thank-you notes in the traditional sense, but rather performance pieces of a sort, meant to charm and entertain. The book also includes a great many letters of apology, written in “sackcloth and ashes,” as he liked to say: to his long-suffering publisher, to friends he feels guilty about neglecting (he procrastinated about letter-writing, too) and one to a girlfriend (John Huston’s wife, as it happened) informing her that he may or may not have given her crabs: “I was suddenly alerted by what felt like the beginnings of troop-movements in the fork, but on scrutiny, expecting an aerial view of general mobilization, there was nothing to be seen, not even a scout, a spy or a dispatch rider.”

In his introduction Sisman says that the letters are written in a “free-flowing prose that is easier and more entertaining to read” than that of Fermor’s travel books, which is true up to a point. The books are so original they take some getting used to. The most famous of them is a three-volume account of a journey Fermor undertook in 1933, when at age 18 he determined to walk all the way from the Netherlands to Constantinople, as he romantically insisted on calling Istanbul. It took him a little over a year, in part because he kept making side trips and detours. He slept in barns and hayricks, and even outdoors once in a while, wrapped in a greatcoat, but more often he stayed in the castles and country houses of Central European nobility, who passed him along, like a mascot, with letters of introduction. He got on not so much by his wits as by his charm, and with youthful avidity he took in everything he saw and heard.

But Fermor didn’t begin writing the first of these volumes, “A Time of Gifts,” until some 40 years later, and the third volume remained unfinished at his death. His account is both immediate and shadowed by the passage of time, evoking a vanished world all but erased by war and the blight of communism. The style is ornate and layered, syntactically complicated, and it sometimes preens right up to the edge of overwriting before pulling itself back with an arresting image or self-deflating observation. Fermor’s friend Lawrence Durrell once described it as “truffled” and dense with “plumage.”

The letters, by contrast, are spontaneous and effortless-seeming, and sparkle — a little too brightly sometimes — with puns and jokes and with the inexhaustible charm that made Fermor such a welcome guest (and bedmate). For American readers his constant name-dropping and favor-currying may prove a little off-putting: The letters are crammed with mention of the rich and titled, who all seem to be marrying and divorcing one another. Sisman, the author of exceptionally good biographies of Boswell, Hugh Trevor-Roper and John le Carré, here in a subsidiary role, provides copious and helpful footnotes not only uncovering Fermor’s many buried literary allusions but also explaining who is who. A typical example, suggesting both the scope and almost incestuous ingrownness of Fermor’s acquaintance: “Professor Derek Ainslie Jackson (1906-82), nuclear physicist and a jockey who rode in the Grand National three times. Among his six wives were Pamela Mitford, Janetta Woolley and Barbara Skelton. He left Janetta for her half sister, Angela Culme-Seymour.”

The best of Fermor’s letters, by and large, are to three women with whom he was not romantically linked but nevertheless formed deep attachments: Lady Diana Cooper; Ann Fleming, wife of Ian, the James Bond novelist; and Deborah Mitford, youngest of the famed Mitford sisters, Duchess of Devonshire and châtelaine of Chatsworth, the great country house where he loved to spend Christmas and rub elbows with the likes of Prince Charles and Camilla. All three women, not coincidentally, were splendid letter writers themselves, and like all great correspondences, Fermor’s with them took on a life and texture of its own. You sometimes feel that they enjoyed one another on the page even more than they could have in person.

It goes without saying that nobody writes letters like this anymore, and it’s a loss. Fermor could never have texted or tweeted, not just because he was a bit of a fogey, but for the same reason he often let weeks pass before answering a letter. He needed to wait until he knew what he wanted to say.

Charles McGrath is a writer and former editor of the Book Review.