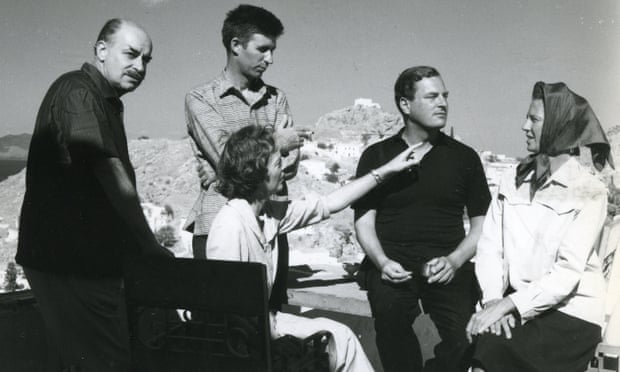

The kidnap gang pose before the action (Courtesy of Estate of William Stanley Moss)

This review of M I Finley’s A World of Odysseus, discusses the hypothesis that oral heroic poetry is not a medium that preserves historical fact, mentioning specifically how the deeds of Paddy, “Billy” Moss, and the others who kidnapped General Kreipe were raised to the level of Cretan heroic oral history, but by 1953, all the names had been forgotten or deliberately erased (the relevant part is highlighted for your convenience).

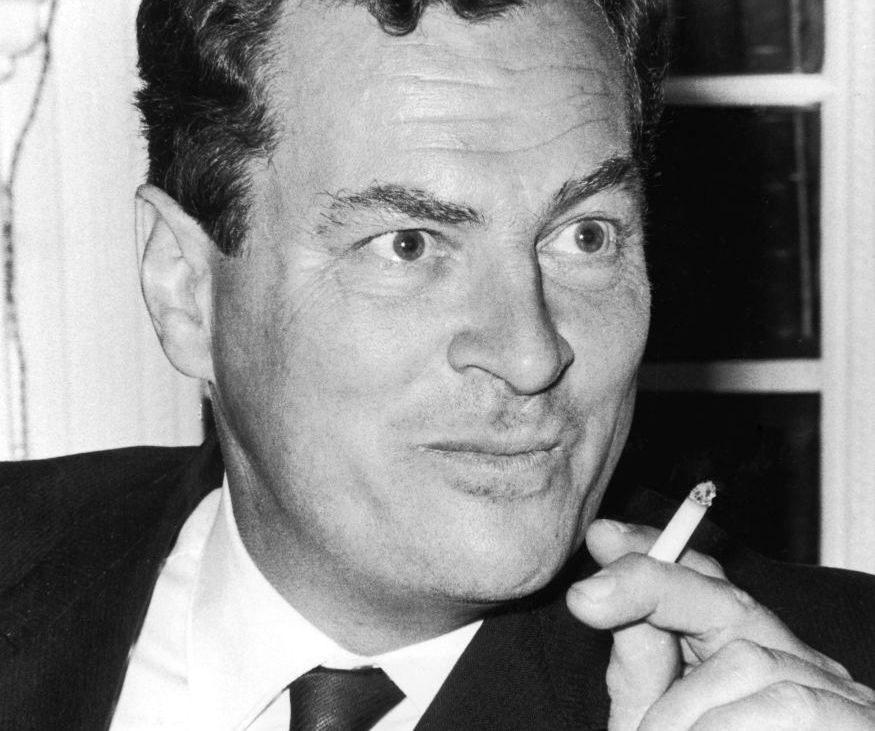

by Bernard Knox

First published in the New York Review of Books

29 Jun 1979

It is now more than two decades since the Professor of Ancient History at Cambridge (who was then an ex-professor from Rutgers) published a book which in a limpid, hard-hitting prose and with a bare minimum of footnotes attempted to draw “a picture of a society, based on a close reading of the Iliad and Odyssey, supported by study of other societies….” This is how Professor Finley characterizes the book now, in the preface to a revised edition which makes only minor changes in the original text but adds two valuable and stimulating appendices, replying to criticism and bringing the argument up to date. He goes on to claim that “the social institutions and values make up a coherent system” which, however strange to us, is “neither an improbable nor an unfamiliar one in the experience of modern anthropology.” The fact that the later Greeks and the nineteenth-century scholars found it incomprehensible on its own terms he dismisses as “irrelevant” and adds that “it is equally beside the point that the narrative is a collection of fictions from beginning to end.”

The ideas here stated in uncompromising terms were implicit in the work from the start. And at the time of its first publication they were not greeted with enthusiasm by the world of Homeric and Bronze Age scholarship. Far from believing that “the narrative was a collection of fictions,” most scholars of the subject found in the Bronze Age remains excavated on the Homeric sites a confirmation of the historicity of the tale of Troy, at least in its main outlines, and went on to search the text of the poems for objects described that might match the objects discovered. Almost simultaneously with the publication of Finley’s book, the decipherment of the Linear B tablets by Ventris and Chadwick seemed to provide the definitive proof that the Homeric poems preserved historical facts of the thirteenth century BC. Here were clay tablets, inscribed in a form of Greek that bore striking resemblances to the Homeric literary dialect, which contained lists of chariots, corslets, and helmets and such Homeric names as Hektor, Achilleus, Aias, Pandaros, and Orestes. John Chadwick recently took a wry backward look at the euphoria of those early days:

The revelation of the Mycenaean archives fostered wild hopes that one day we might come across, let us say, the muster of ships at Aulis for the expedition against Troy or an operation order for the attack of the Seven against Thebes.1

Finley remained one of what he calls a “heretical minority”; and it soon became apparent that the decipherment of Linear B, far from confirming the thesis that the Homeric poems were a reflection of Mycenaean society, had in fact dealt that thesis a fatal blow. It is hard to think of Homer’s Agamemnon as living in the same world with that wanax of Pylos, whose scribes duly recorded that “Kokalos repaid the following quantity of olive oil to Eumedes: 648 liters; from Ipsewas 38 stirrup-jars.” The bureaucratic inventories of the Bronze Age palaces resemble the detailed records of the Near Eastern civilizations which preceded them and the intricate accounting of the later Ptolemaic papyri, but anything more alien to the mentality of illiterate freebooters such as Achilles and equally illiterate pirates such as Odysseus can hardly be imagined.

The tablets also demonstrated that the precise geographical description of Nestor’s kingdom at Pylos which is offered in Book II of the Iliad bears practically no relation to the Mycenaean facts; the conclusion, that the poet or poets knew little or nothing of western Greece, might already have been surmised from the confused and confusing Homeric descriptions of the hero’s homeland, Ithaca. And meanwhile, quite apart from the tablets, it was becoming steadily clearer to all but the most stubborn that there was very little in the archaeological record which would serve to connect the world of the poems with the Bronze Age.

Finley, in the preface to the new edition, contents himself with a very restrained, “I told you so”; he “cannot resist pointing out that proper concern for social institutions and social history had anticipated what philology and archaeology subsequently found.” In The Mycenaean World, John Chadwick heads his penultimate chapter “Homer the Pseudo-Historian” and concludes it with the sentence: “to look for historical fact in Homer is as vain as to scan the Mycenaean tablets in search of poetry; they belong to two different universes.”

Oral heroic poetry is not a medium that preserves historical fact—as Finley pointed out, with a reference to the Chanson de Roland, which made out of a Basque attack on Charlemagne’s rear-guard an assault by Muslim beys and pashas, all carefully identified by names which are “German, Byzantine, or made-up.” A modern example, from the Second World War and from Greece itself, strengthens his case and gives a fascinating glimpse of epic “history” in the making.

In 1953 the late Professor James Notopoulos was recording oral heroic song in the Sfakia district of western Crete, where illiterate oral bards were still to be found. He asked one of them, who had sung of his own war experience, if he knew a song about the capture of the German general and the bard proceeded to improvise one. The historical facts are well known and quite secure. In April 1944 two British officers, Major Patrick Leigh Fermor and Captain Stanley Moss, parachuted into Crete, made contact with Cretan guerrillas, and kidnapped the German commanding general of the island, one Karl Kreipe.

The general was living in the Villa Ariadne at Knossos, the house Evans had built for himself during the excavations. Every day, at the same time, the general was driven south from the Villa to the neighboring small town of Arkhanes, where his headquarters were located. He came home every night at eight o’clock for dinner. The two British officers, dressed in German uniforms, stopped the car on its way home to Knossos; the Cretan partisans overpowered the chauffeur and the general. The two officers then drove the car through the German roadblocks in Heraklion (the general silent with a knife at his throat) and left the car on the coast road to Rethymo. They then hiked through the mountains to the south coast, made rendezvous with a British submarine, and took General Kreipe to Alexandria and on to Middle East Headquarters in Cairo.

Here, in Notopoulos’s summary, is the heroic song the bard produced:

“An order comes from British and American headquarters in Cairo to capture General Kreipe, dead or alive; the motive is revenge for his cruelty to the Cretans. A Cretan partisan, Lefteris Tambakis (not one of the actual guerrilla band) appears before the English general (Fermor and Moss are combined into one and elevated in rank) and volunteers for the dangerous mission. The general reads the order and the hero accepts the mission for the honor of Cretan arms. The hero goes to Heraklion, where he hears that a beautiful Cretan girl is the secretary of General Kreipe.

“In disguise the partisan proceeds to her house and in her absence reads the [English] general’s order to her mother. When the girl returns he again reads the general’s order. Telling her the honor of Crete depends on her, he catalogues the German cruelties. If she would help in the mission, her name would become immortal in Cretan history. The girl consents and asks for three days time in which to perform her role. To achieve Cretan honor she sacrifices her woman’s honor with General Kreipe in the role of a spy. She gives the hero General Kreipe’s plans for the next day.

“Our hero then goes to Knossos to meet the guerrillas and the English general. ‘Yiassou general,’ he says. ‘I will perform the mission.’ The guerrillas go to Arkhanes to get a long car with which to blockade the road. Our hero, mounted on a horse by the side of the blockading car, awaits the car of Kaiseri (that is what the bard calls Kreipe). The English general orders the pistols to be ready. When Kreipe’s car slows down at the turn he is attacked by the guerrillas. Kreipe is stripped of his uniform (only his cap in the actual event) and begs for mercy for the sake of his children (a stock motif in Cretan poetry).

“After the capture the frantic Germans begin to hunt with dogs (airplanes in the actual event). The guerrillas start on the trek to Mount Ida and by stages the party reaches the district of Sfakia (the home of the singer and his audience; actually the general left the island southwest of Mount Ida). The guards have to protect the general from the mob of enraged Sfakians. Soon the British submarine arrives and takes the general to Egypt. Our bard concludes the poem with a traditional epilogue—that never before in the history of the world has such a deed been done. He then gives his name, his village, his service to his country.”2

So much for epic history. Nine years after the event the British protagonists have been reduced to one nameless general whose part in the operation is secondary and there can hardly be any doubt that if the song is still sung now the British element in the proceedings is practically nonexistent—if indeed it managed to survive at all through the years in which Britain, fighting to retain its hold on Cyprus, became the target of bitter hostility in Greece and especially among the excitable Cretans.

It took the Cretan oral tradition only nine years to promote to the leadership of the heroic enterprise a purely fictitious character of a different nationality. This is a sobering thought when one reflects that there is nothing to connect Agamemnon, Achilles, Priam, and Hector with the fire-blackened layer of thirteenth-century ruins known as Troy VII A (the archaeologists’ candidate for Homer’s city) except a heroic poem which cannot have been fixed in its present form by writing until the late eighth century, at least four illiterate centuries after the destruction.

Finley’s professional interest in the poems lies in their value as a source for knowledge of the Dark Ages (so-called because we know almost nothing about them) which intervene between the destruction of the Mycenaean palaces around 1200 BC and the beginning of a new literacy some time in the late eighth century. If the poems contain no memory of historical events of the Bronze Age and, furthermore, do not reflect the civilization, customs, social relationships, or even the material objects of the Bronze Age, what do they have to tell us? Finley’s answer was (and still is) that the poems preserve, with the anachronisms and misunderstandings inevitable in a fluid oral tradition, the social institutions and values of the early Dark Ages, the tenth and ninth centuries BC. “The choice,” as he poses the question in the new edition, “lies between that period and the poet’s own time, now that the ground beneath a supposed Mycenaean world of Odysseus has been removed by the Linear B tablets, assisted by continuous archaeological excavation and study.”

The “poet’s own time” he takes to be the mid-eighth century (a date with which few will quarrel) and makes the claim that the poems fail to reflect the known social conditions of that period. “The polis (city-state) form of political organization” was “widespread in the Hellenic world by then, at least in embryonic form. Yet neither poem has any trace of a polis in its political sense.” Further, the “Phoenician monopoly of trade” in the Odyssey is a reflection of “the period before 800 BC, for by that date the presence of Greek traders in the Levant is firmly attested.” Finley sees no reason to find in Homer’s picture of the sea-lords of Phaeacia a “reflection of the Greek western colonization movement contemporary with Homer,” as many have done: “Magical ships that powered themselves were not instruments of the westward colonization, nor did magic gardens await the migrants on arrival.”

The epic poets are the guardians, preservers, and renewers of a heroic tradition and though they often admit anachronistic details or misunderstand the use or nature of archaic objects, they maintain intact, so Finley insists, the social context in which the heroes can live their larger life. From that context he constructed a model, to use his own formula, “imperfect, incomplete, untidy, yet tying together the fundamentals of a political and social structure with an appropriate value system in a way that stands up to a comparative analysis.” The most striking and original feature of this presentation (organized in chapters headed: “Wealth and Labor”; “Household, Kin, and Community”; “Morals and Values”) is his discussion of the “institution of gift-exchange.”

No reader of the Odyssey can have failed to be amazed and puzzled by the central role gifts play in the social relationships of the characters. Telemachus at Sparta, a young provincial with very uncertain prospects visiting the splendid court of Menelaus and Helen, is offered a parting gift of horses. He declines, on the grounds that his native island is no place to graze horses, and asks for something else: “Give me something that can be stored up.” Menelaus is delighted with his frankness and gives him a bowl made of silver and gold. There are many such encounters in the Homeric poems and readers seeking some explanation of the generosity and especially of the unashamed claims made on it usually found themselves fobbed off with a discussion of Homeric hospitality and the guest-friend relationship. Finley put it firmly in a familiar anthropological context.

The word “gift” is not to be misconstrued. It may be stated as a flat rule of both primitive and archaic society that no one ever gave anything, whether goods or services or honors, without proper recompense, real or wishful, immediate or years away, to himself or to his kin. The act of giving was, therefore, in an essential sense always the first half of a reciprocal action, the other half of which was a counter-gift.

His persuasive analysis of the working of this form of exchange in the poems was widely accepted; those who objected that it reflected not a society but a “heroic ideal” are given short shrift in the new edition.

The system of gift-giving which Finley identified in the poems was already familiar to anthropologists and sociologists; Marcel Mauss in his Essai sur le don (1925) had analyzed its operation in a wide variety of societies ancient and modern (though not in ancient Greece, to which he made only some half-dozen tangential references in his footnotes). If, as Finley says, “the practice…’does not reflect a society’ but an ‘heroic ideal,’ we are driven to the conclusion that, by a most remarkable intuition, Homer was a predecessor of Marcel Mauss, except that he (or his tradition) invented an institution which nearly three thousand years later Mauss discovered to be a social reality.” Since, he goes on to say, “Tamil heroic poetry of South India reveals a comparable network of gift-giving…,” Homer is not the only “instinctive, premature Marcel Mauss.”

Finley’s arguments from the system’s internal coherence and its recorded existence in real societies are compelling but a lingering doubt may remain. Speaking of the belief in the historical reality of the Trojan War and the Catalogue of Ships firmly held by some scholars who reject his sociological model he asks: “In what respect do they differ from gift-giving in their inherent credibility?” A skeptic might answer: “Not at all. Both the Trojan War and the gift-giving system may be equally unhistorical.” If the epic Muse can forget the palaces, inventories, and geography of Mycenaean Greece, remember the chariots but not how they were used, and fabricate not only a war but the names and personalities of chieftains on both sides, how can we trust her to preserve intact the memory of an intricate social system long since obsolete? Finley’s case would be stronger if the comparative method, to which he so often appeals, could produce a parallel: an oral epic poem which, celebrating heroes of a bygone age, garbles time, place, and material objects but preserves, in recognizable form, a complex system of primitive social institutions.

There is one oral epic which goes far toward meeting these specifications, the Turkish Book of Dede Korkut. The full text has only recently been made available in an English version3 (which may be the reason why Finley, whose mastery of the enormous Homeric literature is demonstrated in his useful critical bibliography, does not seem to be aware of it). The text on which modern editions are based was written in the last quarter of the sixteenth century but there is in existence a summary of the poem which was written down before 1332 and the text contains numerous traces of original versions dating from the tenth century. The book recounts, in a mixture of prose and verse, the deeds of the Oghuz, a tribe which, over many centuries, migrated from lands which are now in the Kazakh, Uzbek, and Turkmen Soviet Socialist Republics to become the ancestors of the Seljuk and Ottoman Turks in western Asia Minor.

In their original home their raiding expeditions were aimed at their neighbors to the north, the shamanistic Kipchaks; the Oghuz were recently converted Muslims (though sometimes pre-Islamic customs remain embedded in the narrative). But the sixteenth-century version retains only occasional reminiscences of the Kipchaks and the geography of the Samarkand area; in it the Oghuz beys now live, hunt, and plunder in western Anatolia, a thousand miles to the west; their infidel enemies “worship a god made from wood” and have churches with monks in them—one of their strongholds is Trebizond, which remained in Byzantine hands until 1461.

The Oghuz nomadic beys are given a nonexistent history; at the same time, the known participation of their descendants in major historical events is utterly ignored. “No reference is made,” say the translators, “to the well-known involvement of the Oghuz in the affairs of the Ghazmanide Dynasty…nor is there any mention whatever of the successive stages by which the Seljuks, of Oghuz origin, conquered Iran and most of Anatolia…during the remainder of the eleventh century.” The action of the epic is, as the translators put it, “mainly fiction” but, as they go on to say, “so well do the legends reflect the pattern of early Oghuz life that they must also be considered documents of cultural and social history.”

One of the institutions of the Oghuz is a spectacular variation of the gift-giving system. Their king, Bayindir Khan, commands the allegiance of the beys, the heroes of the epic; they deliver the booty from their brigand raids to him. Periodically he invites them to sumptuous feasts, at which he “distributes the wealth of the Oghuz, usually in the form of gifts to the beys.” But occasionally the feast was a “plunder banquet.” On these occasions, at the high point of the feast, the Khan would take his wife by the hand and leave; the beys would then help themselves to any of his possessions they fancied. It was, in the story, his failure to invite the Outer Oghuz to a plunder banquet which caused a fratricidal war, the “Götterdämmerung” episode which concludes the saga.

In the years since its first appearance, Finley’s “model” has won wide acceptance; his reconstruction of a Dark Age society from the epic text has even, as he says in his preface, “been the acknowledged starting-point of studies by other historians of society and ideas”—among them J.M. Redfield’s Nature and Culture in the Iliad.4 But Homer is a subject on which no two people can be expected to agree entirely, and it may be objected, without impugning the validity of his main thesis, that Finley pushes too hard against the evidence in his claim that there is no trace in the Odyssey of the “polis in its political sense” and his denial that the wanderings of Odysseus are “a reflection of the Greek western colonization movement contemporary with Homer.”

On the first point he is of course right to rule out the imaginary city of the Phaeacians and also right to deny that the presentation of “walls, docks, temples, and a marketplace” can be treated as “Homer’s recognition of the…rise of the polis.” But the equally imaginary city of Troy in the Iliad does seem to prefigure some features of later social organization—in the procession of the women to the Temple of Athena in Book VI, the debate in the assembly in Book VII, above all in Hector’s devotion to Troy and its people, his sense of his duty to the community. Hector is unique in his loyalty to a larger social unit than the oikos, that extended household which, “together with its lands and goods,” was the basic nucleus of Homeric society.

As for the western wanderings, it is true that there is nothing in the poem “that resembles eighth-century Ischia or Cumae, Syracuse, Leontini or Megara Hyblaea.” There is not very much in Shakespeare’s Tempest which resembles early seventeenth-century Bermuda either, but no one can doubt that the play reflects an age of maritime exploration. The fantastic adventures of Odysseus contain several features which suggest that this part of the poem was originally the saga of a voyage to the East, the voyage of the Argonauts, in fact; why should it have been adapted for a western sea-tale except to please an audience interested, if not in the actual founding of colonies, at any rate in the voyages of exploration which must have preceded their foundation?

These are minor cavils. It is an unmixed pleasure to welcome this new edition of a book which has become a classic in its field, as indispensable to the professional as it is accessible to the general reader, and to look forward to Finley’s further riposte to the criticism which his spirited additions are sure to provoke.

From time to time, the Benaki Museum publishes a supplement to its regular journal, and the 9th Supplement is a masterpiece dedicated to Paddy’s life.

From time to time, the Benaki Museum publishes a supplement to its regular journal, and the 9th Supplement is a masterpiece dedicated to Paddy’s life.